A chiral perspective on how we describe, teach, and encode molecular handedness in the age of artificial intelligence

Prelude

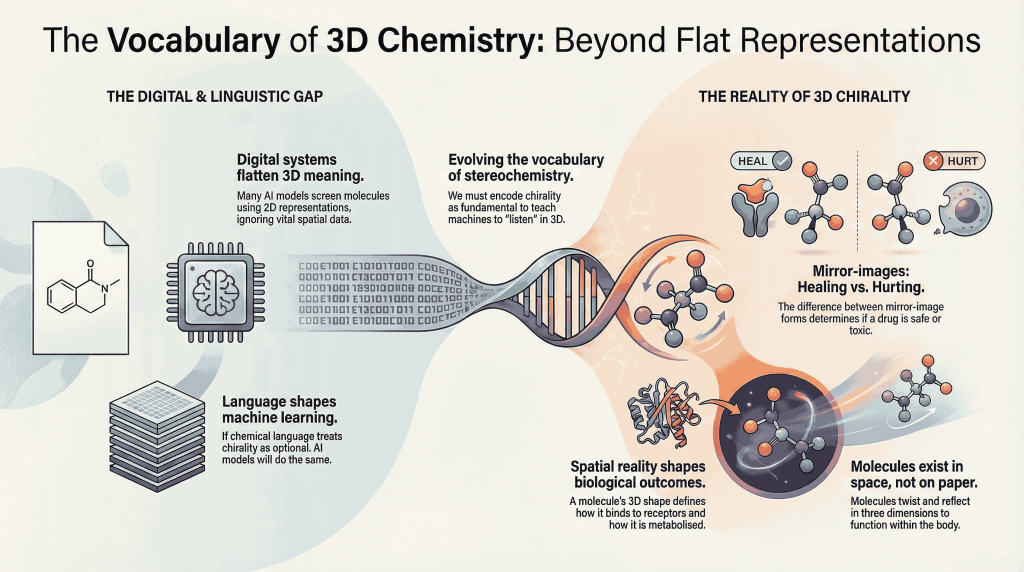

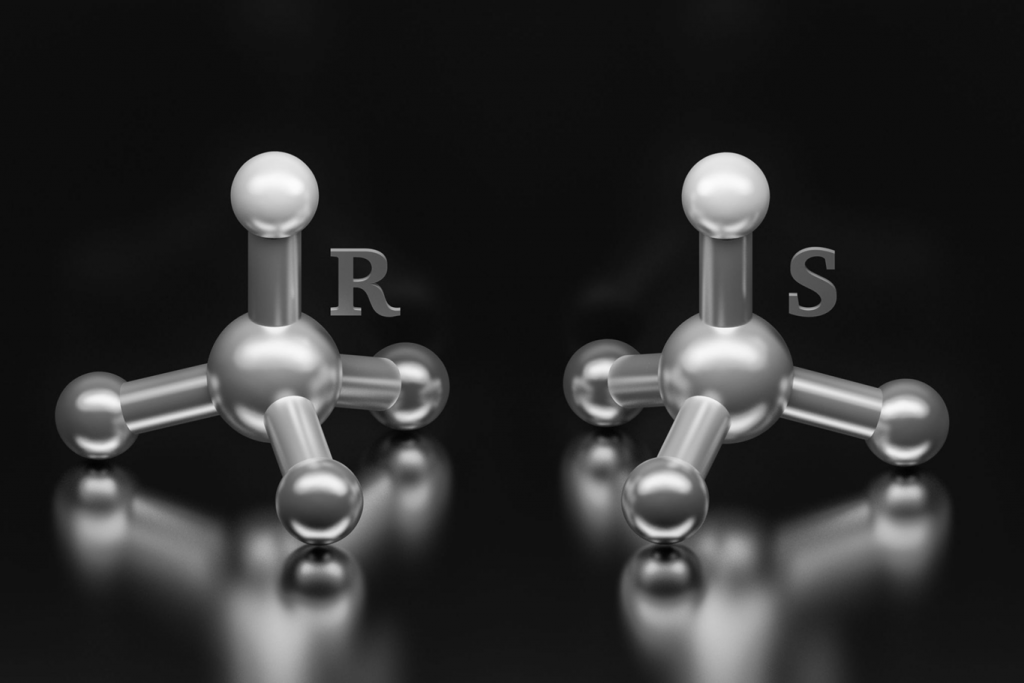

Chiral molecules are not flat drawings on paper (2D). They live in space (3D). They twist, reflect, and occupy three dimensions in ways that decide how they bind to receptors, how they are metabolized, and ultimately how they shape biological outcomes. This spatial reality—what chemists call chirality—has always been at the heart of pharmaceutical science. The difference between two mirror‑image forms of the same molecule can determine whether a drug heals or harms, whether it is processed gently or aggressively, and even whether regulators treat it as one substance or two.

But as artificial intelligence takes center stage in drug discovery, a subtle tension emerges. Many of the digital systems now screening, designing, and evaluating molecules rely on languages and encodings that flatten three‑dimensional meaning into two‑dimensional abstractions. This is not only a technical shortcoming—it is a linguistic one.

The way we name, teach, and encode chirality shapes how students grasp stereochemistry, how researchers curate data, and how machines learn chemistry. If our language treats chirality as optional, our models will inevitably follow. If our language recognizes chirality as fundamental, our technologies will begin to reflect that priority.

This article explores why the vocabulary of stereochemistry must evolve—not just to serve chemists more faithfully, but to help machines listen when molecules speak in three dimensions.

The Hidden Power of Representation

Artificial intelligence does not “see” molecules the way chemists do. It only reads what we provide: strings, graphs, coordinates, descriptors, and annotations. Each of these formats is more than a technical convenience—it is a kind of instruction. Leave out a stereochemical flag, blur a label, or flatten a three‑dimensional encoding, and the model quietly learns that handedness is optional.

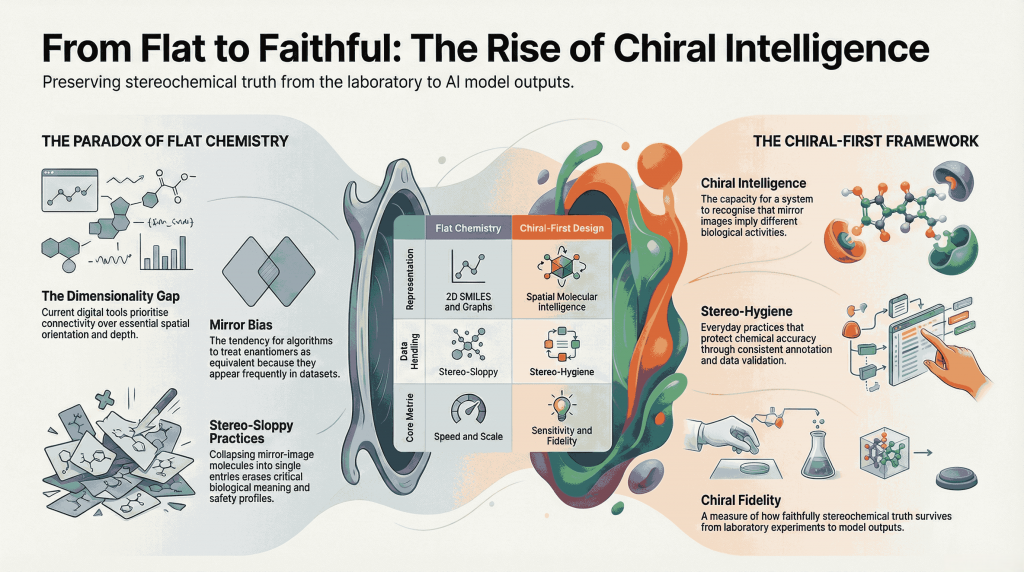

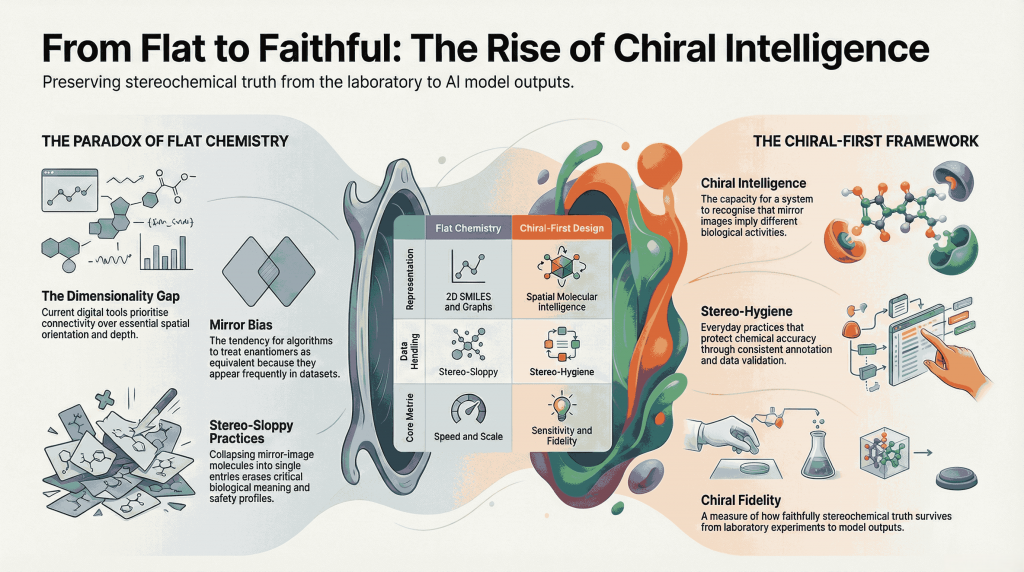

Over time, these small omissions build into larger distortions. Enantiomers collapse into single entries. Racemic mixtures are treated as if they were stereochemically exact. Spatial logic—twists, turns, and orientations—shrinks into a linear alphabet of characters and numbers. The outcome is what might be called stereo‑sloppiness: a cultural and computational habit of treating chirality as a footnote rather than a defining feature.

This is not simply an algorithmic blind spot. It mirrors the way the scientific community itself has historically chosen to describe molecules in digital form.

Why Language Shapes Learning—Human and Machine

For many students, stereochemistry feels less like a puzzle of atoms and more like a puzzle of words. The challenge often lies not in the science itself, but in the way it is described. Labels such as R/S configuration or E/Z isomerism can easily become shorthand to memorize, stripped of the spatial intuition they are meant to convey. What should be a three‑dimensional relationship risks shrinking into a two‑dimensional symbol.

They are chemically identical in composition but distinct in three-dimensional orientation.

Biology recognizes that difference immediately.

The question is — do our digital models? 🧬📐🤖

Interestingly, machines stumble in a similar way. When datasets leave out stereochemical detail, models learn only a blurred, averaged version of molecular behavior. When mirror‑image forms are collapsed into a single identity, algorithms quietly inherit the assumption that handedness is irrelevant.

In both classrooms and computation, meaning slips away at the moment of description.

That is why the language of chirality matters so deeply. It is not just stylistic polish—it is structural. The words we choose shape how stereochemical knowledge travels: through lectures, through databases, and through the pipelines of artificial intelligence.

From Flat Chemistry to Spatial Thinking

For much of modern science, our digital view of molecules has remained stubbornly two‑dimensional. SMILES strings capture how atoms connect, but not how they orient in space. Molecular fingerprints compress rich structures into numerical codes. Graph-based models map nodes and edges, yet leave out depth, twist, and direction.

These representations are fast, powerful, and indispensable—but they were never built to carry the full weight of stereochemistry. And now, as artificial intelligence steps boldly into molecular design, this gap is becoming harder to ignore. AI can sift through millions of compounds, suggest novel scaffolds, and predict bioactivity with remarkable speed. Yet it can still falter at a deceptively simple task: telling a molecule apart from its mirror image.

That tension defines a paradox in today’s drug discovery. Machines give us scale beyond imagination, but sometimes at the cost of spatial awareness—the very dimension where stereochemistry lives and breathes.

The Case for a Stereochemically Explicit Vocabulary

To truly connect molecular reality with digital reasoning, Chiralpedia calls for a more intentional way of talking about chirality.

Instead of treating stereochemistry as a narrow technical detail, this approach frames it as awareness, literacy, and responsibility—spanning chemistry, data science, and AI. The aim is not to discard classical terminology, but to enrich it with a conceptual layer that highlights how chirality is preserved, distorted, or lost across the scientific ecosystem.

Chiral Intelligence

Chiral intelligence is the ability—human or artificial—to recognize when molecular handedness changes meaning. A chiral‑intelligent system doesn’t just rank compounds or predict properties; it understands that mirror images can carry different biological activity, safety profiles, and regulatory consequences. Here, intelligence is measured not by speed or scale, but by sensitivity to stereochemical nuance.

Chiral Literacy

Chiral literacy is fluency in spatial chemical reasoning—the skill of thinking in three dimensions, questioning when stereochemistry has been oversimplified, and noticing when chiral information has been lost in translation. It applies equally to students learning molecular geometry, researchers curating datasets, and developers building AI models. A chiral‑literate workflow expects handedness to be explicit, validated, and preserved.

Chiral Fidelity

Chiral fidelity is about how faithfully stereochemical truth survives the scientific pipeline—from bench experiments to databases, from databases to model inputs, and from models to real‑world decisions. High fidelity means enantiomeric distinctions remain intact; low fidelity signals that meaning has been blurred, averaged, or erased.

Mirror Bias

Mirror bias describes the subtle tendency—human or algorithmic—to treat enantiomers as equivalent, or to favor one stereochemical form simply because it appears more often in data or literature. Naming this bias makes it easier to detect, measure, and correct, rather than letting it persist unnoticed.

Stereo-sloppy

Stereo‑sloppy is a deliberately uncomfortable term for careless handling of stereochemistry—collapsing enantiomers into single entries, omitting configuration labels, or relying on models that flatten three‑dimensional molecular reality into two‑dimensional abstractions. Naming the problem makes it visible, and therefore solvable.

Stereo-hygiene

Stereo‑hygiene refers to everyday practices that safeguard stereochemical accuracy. This includes consistent annotation, validation of configuration labels, careful treatment of racemic versus enantiopure data, and routine checks to ensure chiral information isn’t lost during preprocessing or encoding. Just as data hygiene protects statistical integrity, stereo‑hygiene protects chemical meaning.

Chiral Education

Chiral education extends the idea of teaching stereochemistry beyond formal coursework. It includes how software interfaces display molecules, how databases require or omit stereochemical fields, and how publications communicate chiral results. In this sense, every platform that shows a molecule becomes a classroom.

Chiral-First Design

Chiral‑first design is a forward‑looking philosophy: stereochemistry is treated as a foundational design principle, not a late‑stage correction. In drug discovery, this means considering enantiomeric behavior from the earliest stages of screening. In AI, it means building representations and models that assume chirality matters—because in biology, it always does.

When Words Become Design Principles

Stereochemical terms are not meant to sit quietly in a glossary. They shape how science is practiced. A developer who values chiral intelligence may choose 3D‑equivariant models over faster 2D shortcuts, ensuring that chiral fidelity is preserved. A dataset curator committed to chiral literacy and stereo‑hygiene may refuse to release entries that collapse racemic and enantiopure data into a single label. An educator determined to resist stereo‑sloppiness may rethink how molecular space is taught—placing physical models and spatial reasoning at the center, rather than relying only on flat diagrams.

In this way, language becomes more than description. It becomes infrastructure. It guides what is built, what is trusted, and what counts as “good enough” in scientific practice.

A Mirror for the AI Era – When Language Shapes What Machines Learn

We often say that artificial intelligence reflects the data it is fed. But it also mirrors the concepts we choose to emphasize and the terms we allow to become routine. If chirality is treated as a minor technical detail, machines will learn it as a minor technical detail. If chirality is presented as foundational, machines will begin to treat it as foundational. And if mirror bias remains unnamed, it will quietly persist—woven into datasets, encoded in models, and echoed in predictions.

The evolution of stereochemical language is therefore more than a matter of communication. It is a matter of values. It signals what the scientific community regards as essential—and what it is willing to dismiss as optional—in the digital representation of chemistry.

Looking Forward: Toward Chiral-First Thinking

The next chapter of AI in drug discovery will not be written only in faster algorithms or bigger datasets. Its true shape will come from deeper, more faithful representation.

A chiral‑first perspective imagines a world where enantiomer‑specific information is preserved by default, where models respond with sensitivity to stereochemical shifts, where generative systems actively explore chiral chemical space instead of skirting around it, and where education places spatial reasoning at the core of scientific training.

In such a future, artificial intelligence does more than process molecules. It engages with them—entering into a stereochemically aware dialogue that respects the twists, reflections, and orientations that define molecular identity.

Closing Reflection

At its core, chirality reminds us that the smallest twists in space can change everything. An enantiomeric turn may decide whether a molecule heals or harms, while lapses in stereo‑hygiene can allow subtle errors to slip through unnoticed. As artificial intelligence begins to share in these decisions, it inherits not only our datasets but also our language—absorbing what we guard with chiral fidelity, what we overlook under mirror bias, and how we value diastereomeric distinctions in design.

To evolve the language of chirality is to evolve the values of digital chemistry itself. It means embracing chiral‑first design, where molecular handedness is not a footnote but the central narrative of how chemistry touches life. And perhaps, as we teach machines to listen more carefully to stereochemical nuance, we also remind ourselves to speak with greater precision—about the three‑dimensional reality in which chemistry has always existed.

References

Moores A, Zuin Zeidler VG. Don’t let generative AI shape how we see chemistry. Nat Rev Chem. 2025 Oct;9(10):649-650. doi: 10.1038/s41570-025-00757-9.

Brian Buntz, How stereo-correct data can de-risk AI-driven drug discovery. https://www.drugdiscoverytrends.com/how-stereo-correct-data-can-de-risk-ai-driven-drug-discovery/. News Release: 15 October, 2025

Yasuhiro Yoshikai, Tadahaya Mizuno, Shumpei Nemoto & Hiroyuki Kusuhara. Difficulty in chirality recognition for Transformer architectures learning chemical structures from string representations. Nat Commun 15, 1197, 2024. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-45102-8

Daniel S. Wigh, Jonathan M. Goodman, Alexei A. Lapkin. A review of molecular representation in the age of machine learning. The WIREs Computational Molecular Science, 12, 5, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1603

Derek van Tilborg, Alisa Alenicheva, Francesca Grisoni. Exposing the Limitations of Molecular Machine Learning with Activity Cliffs. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 23, 5938-5951. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.2c01073

Dagmar Stumpfe, Huabin Hu, Jürgen, Bajorath. Evolving Concept of Activity Cliffs. ACS Omega, 4, 11, 14360-14368, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b02221

Ramsundar, B.; Eastman, P.; Walters, P.; Pande, V. Deep Learning for the Life Sciences: Applying Deep Learning to Genomics, Microscopy, Drug Discovery, and More. O’Reilly Media, 2019. ISBN 9781492039839.

Walters WP, Barzilay R. Applications of Deep Learning in Molecule Generation and Molecular Property Prediction. Acc Chem Res. 2021 Jan 19;54(2):263-270. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00699.

Sanchez-Lengeling B, Aspuru-Guzik A. Inverse molecular design using machine learning: Generative models for matter engineering. Science. 2018 Jul 27;361(6400):360-365. doi: 10.1126/science.aat2663.

Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2

Gaiński, P.; Koziarski, M.; Tabor, J.; Śmieja, M. ChiENN: Embracing Molecular Chirality with Graph Neural Networks. In: Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer, 2023; DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-43418-1_3.

Liu, Y.; et al. Interpretable Chirality-Aware Graph Neural Network for Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship Modeling. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2023.

Yan, J.; et al. Interpretable Algorithm Framework of Molecular Chiral Graph Neural Network for QSAR Modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.4c02259.

Ariens EJ. Stereochemistry, a basis for sophisticated nonsense in pharmacokinetics and clinical pharmacology. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 1984 26, 663 to 668.

Kruithof, P.; et al. “Practical aspects of stereochemistry in cheminformatics and molecular modeling.”

Journal of Cheminformatics 2021, 13, 1–26. doi: 10.1186/s13321-021-00519-8

Fourches, D.; Muratov, E.; Tropsha, A. “Trust but verify: on the importance of chemical structure curation in cheminformatics.” J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 1189–1204. doi: 10.1021/ci100176x

Zdrazil B, Felix E, Hunter F, Manners EJ, Blackshaw J, Corbett S, de Veij M, Ioannidis H, Lopez DM, Mosquera JF, Magarinos MP, Bosc N, Arcila R, Kizilören T, Gaulton A, Bento AP, Adasme MF, Monecke P, Landrum GA, Leach AR. The ChEMBL Database in 2023: a drug discovery platform spanning multiple bioactivity data types and time periods. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024 Jan 5;52(D1):D1180-D1192. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad1004.

Schuett KT, Kindermans PJ, Sauceda HE, et al. SchNet: a continuous filter convolutional neural network for modeling quantum interactions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (2017), pp. 992-1002. doi/10.48550/arXiv.1706.08566

Testa B, Trager WF. Drug Metabolism: Chemical and Enzymatic Aspects. CRC Press, 1995.

Tom G, Yu E, Yoshikawa N, Jorner K, Aspuru-Guzik A. Stereochemistry-aware string-based molecular generation. PNAS Nexus. 2025 Oct 14;4(11):pgaf329. doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf329.

Yaëlle Fischer, Thibaud Southiratn, Dhoha Triki, Ruel Cedeno. Deep Learning vs Classical Methods in Potency & ADME Prediction: Insights from a Computational Blind Challenge. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5c01982.

Schneider N, Lewis RA, Fechner N, Ertl P. Chiral Cliffs: Investigating the Influence of Chirality on Binding Affinity. ChemMedChem. 2018 Jul 6;13(13):1315-1324. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201700798.

Husby J, Bottegoni G, Kufareva I, Abagyan R, Cavalli A. Structure-based predictions of activity cliffs. J Chem Inf Model. 2015 May 26;55(5):1062-76. doi: 10.1021/ci500742b.

Further Reading

Eliel, E. L., & Wilen, S. H. Stereochemistry of organic compounds. John Wiley & Sons. 1994.

Eliel & Wilen repeatedly caution that “sloppy usage of stereochemical terms” leads to incorrect interpretation of structure, properties, and reactivity. They emphasize that stereochemical descriptors must be used precisely and consistently, and warn instructors to avoid careless or ambiguous usage.

Nguyen, L. A.; He, H.; Pham-Huy, C. Chiral Drugs: An Overview. International Journal of Biomedical Science, 2006, 2, 85–100. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.2.85 – Foundational overview of chirality, enantiomer-specific pharmacology, and clinical relevance.

Ariëns, E. J. Stereochemistry, a Basis for Sophisticated Nonsense in Pharmacokinetics and Clinical Pharmacology. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 1984, 26, 663–668. doi: 10.1007/BF00541922 – Classic critique highlighting the dangers of ignoring stereochemistry in drug development.

FDA Guidance for Industry. Development of New Stereoisomeric Drugs. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 1992.DOI: 10.1037/e547072006-001 – Regulatory cornerstone establishing stereochemical expectations in drug approval.

Schneider, G. Automating Drug Discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2018, 17, 97–113. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.232

Conceptual framing of automation, interpretation, and responsibility in AI-driven discovery.

Smith, S. W. Chiral Toxicology: It’s the Same Thing…Only Different. Toxicological Sciences, 2009, 110, 4–30. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp097

Clear discussion of enantiomer-specific toxicity and biological divergence.

https://chiralpedia.com/glossary.php

Chiralpedia Glossary Box – The Language of Chiral thinking

Chiral Intelligence

The capacity of a human or machine system to recognize, interpret, and act on stereochemical differences as meaningful biological and chemical signals, not as optional structural details.

Chiral Literacy

Fluency in spatial chemical reasoning—the ability to understand, question, and preserve stereochemical meaning across education, data curation, modeling, and communication.

Chiral Fidelity

The degree to which stereochemical truth is preserved as molecular information moves from experiment to database, from database to model, and from model to decision.

Mirror Bias

A systematic tendency—human or algorithmic—to treat enantiomers as equivalent or to favor one stereochemical form due to skewed data representation or incomplete training.

Stereo-Sloppy

A descriptive term for careless handling of stereochemistry, such as collapsing enantiomers into single entries, omitting configuration labels, or flattening 3D molecular information into 2D abstractions.

Stereo-Hygiene

Best practices for maintaining accurate, explicit, and consistent stereochemical information in datasets, publications, and computational workflows.

Chiral Education

An expanded view of teaching stereochemistry that includes how students learn spatial reasoning, how datasets are annotated, how AI models are designed, and how research communicates molecular handedness.

Chiral-First Design

A philosophy in drug discovery and AI development where stereochemistry is considered a foundational design constraint rather than a late-stage correction.