❓ Can AI truly be intelligent if it is stereo-blind? 🌀

On Visuals and Stereochemical Truth

Some illustrations in this series are generated or assisted by AI to support conceptual understanding. These visuals are intentionally simplified and should not be read as stereochemically rigorous or chemically exact representations. Wherever stereochemical fidelity matters, it is addressed explicitly in the discussion—because in chemistry, especially in chiral systems, intuition must always yield to structure.

The earlier episodes treated chiral bias as a technical defect. The data were messy, the representations flattened three dimensional reality, and the models inherited those flaws. Those problems can be addressed with better data, better features and better architectures.

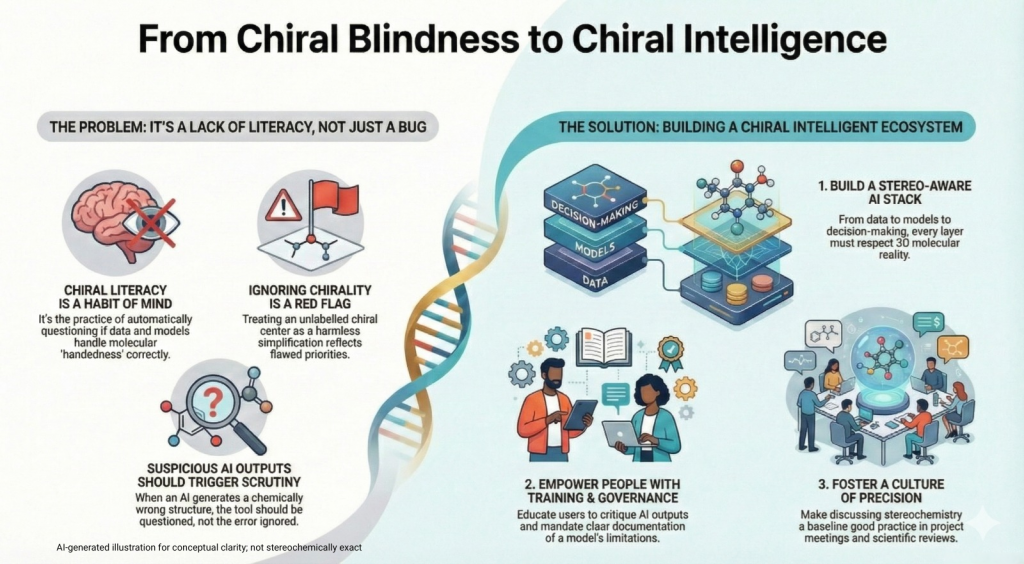

This final episode argues that something broader is at stake. It introduces the idea of chiral literacy as a property of teams and institutions. It sketches what a fully chiral intelligent AI stack looks like and how it changes decision making. It then looks at education and governance, drawing on Moores and Zuin Zeidler’s concerns about how generative AI is already starting to reshape chemical intuition. The goal is not only unbiased models, but AI that respects and amplifies the hard won knowledge of stereochemistry instead of eroding it.

5.1 From technical bias to cultural literacy

It is easy to think of chiral bias purely in engineering terms. Clean the data, patch the descriptor code, swap in a better GNN, and the job is done.

That view misses something important.

Decisions about how to store stereochemistry, whether to treat racemates and enantiomers separately, which assays to annotate carefully and which to leave vague, are not just technical details. They reflect what an organization considers important.

If no one on a project team ever asks, “Does this model distinguish R and S here, and does it matter”, then even a well designed model will be used in a way that ignores chirality.

Chiral literacy is a name for the habit of mind that resists that. Someone with chiral literacy:

- Thinks automatically about which stereocenters in a scaffold are likely to matter for binding, metabolism and toxicity.

- Asks whether the data and models treat those centers correctly.

- Treats an unlabelled chiral center or an unspecified racemic mixture as a gap that needs attention, not as a harmless simplification.

- Sees generative proposals with suspicious stereochemistry as a chance to question the tool, not as a minor cosmetic issue.

This attitude is familiar to many medicinal chemists. The difference now is that they have to hold onto it in an environment where AI systems tend to flatten or ignore the very details they care about.

5.2 What a chiral intelligent stack looks like

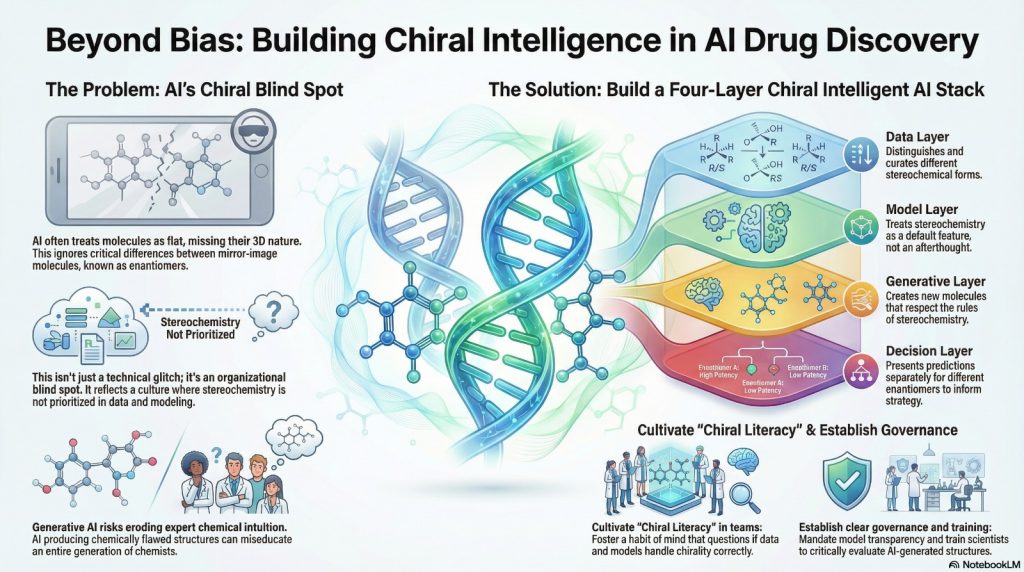

From a systems point of view, a chiral intelligent AI ecosystem has a few clear traits.

- The data layer distinguishes stereochemical forms wherever it matters. Compound identifiers reflect racemate or enantiopure status. Assay records state what was tested. Well known chiral drugs and series are curated stereo specifically.

- The model layer treats stereochemistry as part of the default path. Feature generators that drop stereo are not used silently. Model cards and documentation explicitly describe how enantiomers are represented and handled. Evaluation includes benchmarks that probe chirality, not just generic activity datasets.

- The generative layer respects chirality by construction. Training corpora have stereochemistry cleaned up as much as possible. Novelty calculations neutralise mirror image duplicates unless a project explicitly wants both hands. Molecules with undefined or impossible stereochemistry are flagged or removed automatically.

- The decision layer surfaces enantiomer specific predictions. When teams look at potency or risk reports, they see separate values for different stereochemical forms of interest. Key program meetings explicitly discuss whether to pursue a racemate, a single enantiomer or a chiral switch strategy.

In such an environment, saying “we forgot to consider chirality” sounds as strange as saying “we forgot to consider basic metabolism”.

5.3 Education and Moores and Zuin Zeidler’s critique

Moores and Zuin Zeidler warn that generative AI is already starting to shape how students and non experts think about chemistry. They describe systems that produce neat diagrams of molecules and reactions that are chemically wrong, and argue that if these outputs slip into textbooks, lectures and informal teaching, they can miseducate an entire generation.

Zuin Zeidler has reinforced this in interviews by stressing that understanding how data are created in the lab is essential. If you do not know where a number or a structure came from, you are more likely to trust an AI generated view of chemistry even when it is wrong.

Applied to chirality, this means that education has to cover two things together.

- Classical stereochemistry. R and S, optical rotation, enantioselective synthesis, eutomer and distomer, and all the usual content.

- How stereochemistry is represented in SMILES, graphs and three dimensional models, and how AI systems can get it wrong.

Useful educational exercises might include:

- Asking students to feed both enantiomers of a simple drug into a property predictor and see whether the outputs differ.

- Comparing AI generated structures of chiral molecules with curated reference structures to see where stereocenters are missing or wrong.

- Looking at cases like thalidomide and methadone and asking how an AI system would see those molecules under different representations.

The aim is to train chemists and data scientists who are comfortable interrogating AI output rather than passively consuming it.

5.4 Governance and responsibility

Beyond tools and training there is governance. Responsible use of AI in drug discovery should include basic stereochemistry in its policies.

Examples:

- Model documentation that states clearly whether a system is stereo aware. If a virtual screening model does not distinguish enantiomers, that limitation is written down where users can see it.

- Internal guidelines that for key decisions, especially those involving chiral drugs, teams either use stereo aware models or separately assess the impact of chirality using experimental or mechanistic data.

- Publication and reporting standards that discourage the use of raw AI generated molecular images in papers or slides without expert review of their stereochemistry and valence.

Moores and Zuin Zeidler’s central line, “do not let generative AI shape how we see chemistry“, can be turned into a rule of thumb here. AI is a tool for proposing structures and patterns. Human judgement about chemical plausibility and significance comes first.

5.5 Culture change

Tools, training and governance are all important, but cultural change is what makes chiral literacy stick. Small signals matter.

- In meetings, senior scientists who routinely specify which enantiomer they are talking about send a message that these details matter.

- Data scientists who ask for clarity about racemic versus enantiopure assays show that they are not treating molecules as abstract graphs only.

- Project retrospectives that explicitly ask whether stereochemistry was handled correctly create a norm that this dimension is part of serious review.

Over time, these habits accumulate. New team members absorb them without thinking. Stereochemistry stops being something to bring up only in specialist discussions and becomes part of baseline good practice, even in conversations about AI architecture and benchmark design.

5.6 Where this leaves AI drug discovery?

Stepping back, the picture that emerges is not pessimistic.

- AI has already demonstrated that it can accelerate many parts of discovery.

- The technical aspects of chiral bias are increasingly well understood. Data curation practices, stereo aware feature schemes and chiral sensitive architectures are all active research areas.

- Critiques such as those by Moores and Zuin Zeidler are pushing the field to think harder about how generative models are used and what they do to chemical intuition.

The main challenge now is to bring these threads together. A good target is simple to state.

AI systems used in drug discovery should:

- See molecules in a way that respects their three dimensional, chiral nature.

- Be trained and evaluated on data that make stereochemical distinctions when they matter.

- Be embedded in workflows where chemists and data scientists recognise and question their limitations.

If that is achieved, algorithms will stop missing the mirror and will instead help us navigate a chemical universe where left and right are not interchangeable curiosities, but central facts of molecular life.

References

Moores, Audrey & Zuin Zeidler, Vânia G. (2025). “Don’t let generative AI shape how we see chemistry.” Nature Reviews Chemistry, 9(10), 649–650. doi: 10.1038/s41570-025-00757-9

Zuin Zeidler, V. (2025, November 10). Chemistry and AI: Good data are gold [Interview]. Leuphana University Lüneburg. Retrieved from https://www.leuphana.de/en/institutions/faculty/sustainability/news/single-view/2025/11/10/chemistry-and-ai-good-data-are-gold.html

Zhou J, Zhang C, Zhang H, et al. Are deep learning models aware of chirality A case study on molecular property prediction. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 2022 62, 1108 to 1121.

Gaiński, P.; Koziarski, M.; Tabor, J.; Śmieja, M. ChiENN: Embracing Molecular Chirality with Graph Neural Networks. In: Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer, 2023; DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-43418-1_3.

Liu, Y.; et al. Interpretable Chirality-Aware Graph Neural Network for Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship Modeling. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2023.

Yan, J.; et al. Interpretable Algorithm Framework of Molecular Chiral Graph Neural Network for QSAR Modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jcim.4c02259.

Tom, G., Yu, E., Yoshikawa, N., Jorner, K., Aspuru-Guzik, A., et al. (2025). Stereochemistry-aware string-based molecular generation. PNAS Nexus, 4(11), pgaf329. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf329

Bronstein MM, Bruna J, LeCun Y, Szlam A, Vandergheynst P. Geometric deep learning: grids, groups, graphs, geodesics and gauges. Nature Reviews Machine Intelligence. 2021 2, 743 to 755. doi: :10.48550/arXiv.2104.13478

Yaëlle Fischer, Thibaud Southiratn, Dhoha Triki, Ruel Cedeno. Deep Learning vs Classical Methods in Potency & ADME Prediction: Insights from a Computational Blind Challenge. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.5c01982.

Schneider N, Lewis RA, Fechner N, Ertl P. Chiral Cliffs: Investigating the Influence of Chirality on Binding Affinity. ChemMedChem. 2018 Jul 6;13(13):1315-1324. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201700798.

Husby J, Bottegoni G, Kufareva I, Abagyan R, Cavalli A. Structure-based predictions of activity cliffs. J Chem Inf Model. 2015 May 26;55(5):1062-76. doi: 10.1021/ci500742b.

Further Reading