Can an AI truly understand a molecule if it cannot tell left from right?

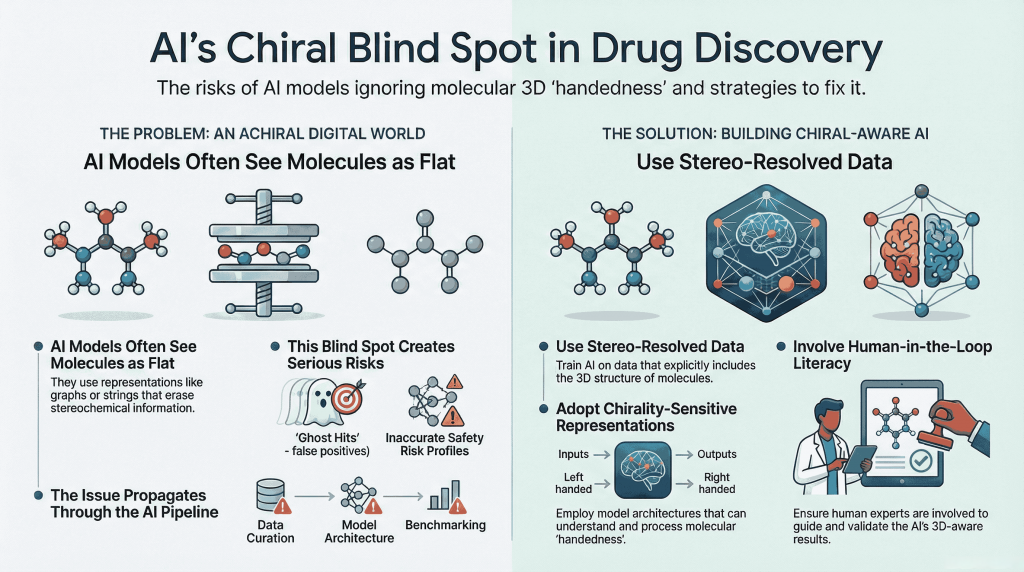

Artificial intelligence now shapes the earliest and most consequential stages of drug discovery, from virtual screening and ADMET prediction to generative molecular design. Yet many of these systems operate in an effectively achiral digital environment, where molecules are represented as flat graphs, strings, or feature vectors that often erase or blur stereochemical information. This article introduces the concept of chiral bias as an information and representation problem rather than a purely algorithmic one. It traces how the loss of molecular handedness propagates through data curation practices, model architectures, and benchmarking conventions, and shows how this blind spot leads to ghost hits, averaged risk profiles, and hollow novelty in generative workflows. Finally, it outlines practical strategies for building chiral-aware pipelines—combining stereo-resolved data, chirality-sensitive representations, and human-in-the-loop literacy—to ensure that AI systems respect the three-dimensional reality of bioactive molecules rather than flattening it.

Introduction — When Digital Chemistry Forgets the Mirror

Artificial intelligence now sits at the center of early-stage drug discovery. Machine learning models rank millions of virtual molecules, predict binding affinities, anticipate metabolic liabilities, and even generate entirely new chemical structures. The promise is compelling: faster timelines, broader chemical exploration, and more informed decisions before a single compound is synthesized.

Yet beneath this technological confidence lies a quiet conceptual gap. Many of these systems are trained and evaluated in what is effectively an achiral digital universe—one in which molecules are treated as flat graphs, strings, or feature vectors rather than as three-dimensional, handed objects. In this universe, left and right often collapse into one.

This article examines what happens when AI-driven drug discovery “forgets the mirror.” It introduces the idea of chiral bias as an information and representation problem, follows its consequences across virtual screening, ADMET prediction, and generative design, and outlines practical steps toward building systems that treat molecular handedness as a first-class scientific feature rather than a decorative detail.

1. The Digital Turn in Molecular Discovery

Over the last decade, computational chemistry has shifted from a supporting role to a defining force in early discovery. Deep learning models now predict molecular properties directly from structure, score docking poses, and generate candidate molecules that attempt to balance potency, solubility, and synthetic accessibility. Protein structure prediction systems feed atomic-level models into structure-based design pipelines, closing the loop between sequence, structure, and small-molecule optimization.

This scale of computation changes the nature of scientific judgment. Instead of chemists exploring a handful of hand-designed ideas, teams navigate landscapes defined by algorithmic filters and rankings. What the model can represent becomes what is considered plausible. What it cannot represent gradually disappears from view.

In this sense, AI does more than accelerate discovery. It shapes the conceptual boundaries of chemical space within which human decisions are made. Chirality—subtle, three-dimensional, and often under-annotated—sits uncomfortably at the edge of those boundaries.

2. Chirality in Plain Terms — Why Left and Right Matter

A molecule is chiral if its mirror image cannot be superimposed on it, like left and right hands. These mirror-image forms, known as enantiomers, share the same atoms and connectivity but differ in their three-dimensional arrangement in space.

In an achiral environment, enantiomers often share many physical properties. Biology is not achiral. Proteins are built from L-amino acids. DNA adopts a right-handed helix. Enzymes, receptors, and transporters are chiral objects, and they frequently interact very differently with the two hands of a molecule.

Classic pharmacological examples still define the field:

- Salbutamol: The R-enantiomer is a bronchodilator; the S-form is inactive at the receptor.

- Methadone: The R-enantiomer drives most of the desired analgesic effect, while the S-enantiomer is closely associated with hERG channel binding and QT prolongation risk.

- Thalidomide: A historical reminder that small stereochemical differences can have devastating biological consequences.

Medicinal chemists therefore think naturally in terms of eutomer and distomer, chiral switches, and enantioselective metabolism. The question this article poses is simple but consequential: do the AI systems that increasingly shape discovery workflows share this three-dimensional understanding, or do they flatten it into abstraction?

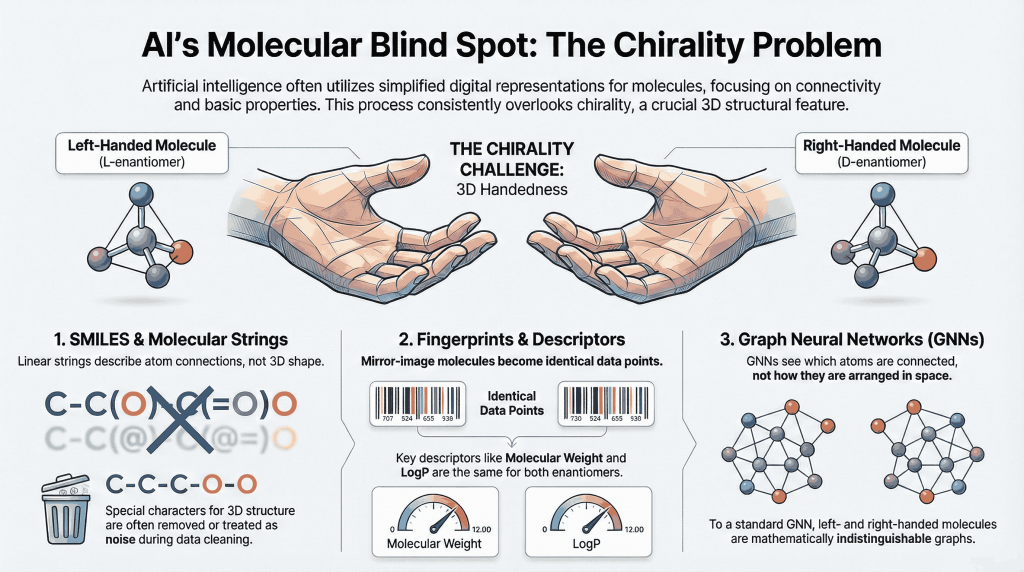

3. How AI “Sees” Molecules

AI models do not see molecules as chemists do. They see representations—formal encodings designed to make chemistry computable. Three families dominate modern pipelines.

3.1 SMILES and Molecular Strings

SMILES encodes molecular connectivity as a linear string. In principle, stereochemistry can be represented using special tokens for tetrahedral centers and double-bond geometry. In practice, historical datasets often omit or inconsistently apply these markers. During canonicalization and cleaning, stereochemical annotations are frequently stripped or normalized away.

For language models trained on such corpora, chirality becomes a rare and weak signal—more like punctuation than chemistry. The model learns to predict patterns of connectivity and functional groups while treating handedness as noise.

3.2 Fingerprints and Descriptors

Extended connectivity fingerprints and common physicochemical descriptors summarize molecular structure into fixed-length vectors. Many default implementations ignore stereochemistry entirely. LogP, molecular weight, polar surface area, and topological counts are identical for both enantiomers. If these features dominate the input, R and S literally become the same point in feature space.

3.3 Graph Neural Networks

Graph-based models represent atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. They are designed to be invariant to how the graph is labeled—only connectivity matters. Enantiomers are graph-isomorphic: their adjacency matrices differ only by a relabeling of atoms. Without explicit stereo-aware features or three-dimensional information, a graph neural network has no mathematical way to tell left from right.

Across these representations, the pattern is consistent. Chirality is not actively removed; it is simply never carried through the pipeline in a way that models can reliably learn from it.

4. Chiral Bias as an Information Problem

We often associate “bias” in AI with social or ethical concerns. In molecular science, chiral bias arises from a different source: systematic loss of information.

The pattern repeats across organizations and datasets:

- Racemates and enantiomers are merged into single records.

- Assay metadata fail to specify which stereochemical form was tested.

- Feature generation pipelines drop stereochemistry by default.

- Benchmarks rarely ask models to distinguish mirror images.

The result is a digital world in which molecules are effectively achiral. Models trained in this world learn patterns that are chemically reasonable on average, but blind to enantioselective reality.

This is not an academic curiosity. It changes which molecules are designed, which risks are perceived, and which projects move forward.

5. Virtual Screening — Ghost Hits and Invisible Eutomers

In a typical virtual screening workflow, a model scores a large library of molecules and ranks them for follow-up. If the representation hides stereochemistry, the model learns an averaged view of activity.

Consider a chiral scaffold where one enantiomer binds strongly and the other weakly. If historical labels mix racemic and enantiopure assays, the model sees only a moderate “on average” signal. When it evaluates new analogues, both hands receive similar scores.

In structure-based workflows, docking and machine-learned scoring functions can show the same effect. If subtle three-dimensional clashes in a chiral pocket are not captured by the scoring function, mirror-image ligands can be ranked similarly even when visual inspection reveals that one cannot fit the binding site.

The output is a hit list populated by ghost molecules—candidates that look promising numerically but are doomed by construction once synthesized. At the same time, the true eutomer fails to stand out as strongly as it should.

6. ADMET — Risk Profiles Blurred by Averaging

Chiral bias becomes more consequential in pharmacokinetics and safety prediction. Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and toxicity are often enantioselective. One hand of a molecule may be rapidly cleared while the other persists. One may bind off-target receptors that the other avoids. One may form reactive metabolites while the other does not.

If an ADMET model is trained on data that treats “the drug” as a single entity, and if its representation ignores stereochemistry, it can only learn an average risk profile—one that may correspond to no real formulation.

In the case of methadone, averaging masks the fact that cardiac risk is primarily associated with the S-enantiomer, while analgesic efficacy resides largely in the R-form. A stereo-blind model cannot meaningfully distinguish a hypothetical enantiopure strategy from the racemate.

When such models are used early in pipelines to flag or clear compounds, this averaging becomes a systemic distortion of risk perception.

7. SAR — When Cliffs Disappear

Medicinal chemists rely on structure–activity relationships (SAR) as a navigational map. They look for smooth trends that suggest reliable optimization pathways and for sharp cliffs that signal where small structural changes lead to large biological consequences. Chiral bias distorts both features of the map.

7.1 Averaging Away Enantioselective Reality

When R and S enantiomers are merged into a single representation, the model is forced to reconcile conflicting labels. If one hand is highly potent and the other weak, the learned signal becomes a moderate average. In practice, this means the model concludes that the region around the stereocenter is unimportant, even when experimental chemistry says it is critical.

The effect is subtle. Visualizations of predicted versus observed activity still look reasonable. Global performance metrics remain high. Yet the local structure of the SAR—precisely where chemists make design decisions—has been flattened.

7.2 False Smoothness and Misleading Trends

This averaging introduces what might be called false smoothness. The model presents a continuous gradient of activity across a series, suggesting that incremental changes will lead to incremental improvements. In reality, the underlying chemical landscape may be discontinuous, with steep jumps in potency or selectivity tied to stereochemical configuration.

For project teams, this can be deeply misleading. Resources are allocated along apparently promising optimization pathways that, in the laboratory, repeatedly fail because the critical stereochemical dimension is missing from the model’s internal representation.

7.3 Implications for Chiral Switches and Lead Optimization

Chiral switches—strategies that replace a racemate with a single, better-behaved enantiomer—depend on identifying and exploiting enantioselective differences in efficacy, safety, or pharmacokinetics. A stereo-blind SAR model cannot support this strategy. It cannot highlight which stereocenters are worth controlling synthetically or which configurations drive therapeutic benefit.

In lead optimization, this can lead to a systematic undervaluation of stereochemical control. Synthetic effort is directed toward peripheral substitutions rather than toward the more challenging, but potentially more rewarding, task of controlling three-dimensional configuration.

7.4 A Diagnostic Question for Teams

A practical way to surface this problem is to ask a simple diagnostic question during SAR reviews:

If we were to invert this stereocenter, does the model predict any meaningful change? If the answer is consistently no across a chiral series, the issue may not be that chirality is unimportant, but that the model cannot see it. In this sense, SAR is not just an output of AI systems. It is a test of their stereochemical literacy.

8. Generative AI — Novelty Without Meaning

Generative models promise to expand chemical imagination. When chirality is mishandled, that novelty becomes hollow. Stereo-blind systems tend to:

- Propose mirror images as distinct “new” molecules.

- Generate structures with undefined stereocenters at chemically critical positions.

- Produce molecules that look plausible in two dimensions but cannot exist as drawn in three.

There is also a cultural dimension. When AI-generated molecules populate slides, reports, and teaching materials, they quietly teach what counts as normal chemistry. If handedness is treated as optional or cosmetic, that attitude spreads—especially among students and non-specialists who may not yet have the experience to question what they see.

Critics of generative AI in chemistry have warned that the risk is not merely incorrect outputs, but a gradual reshaping of chemical intuition itself.

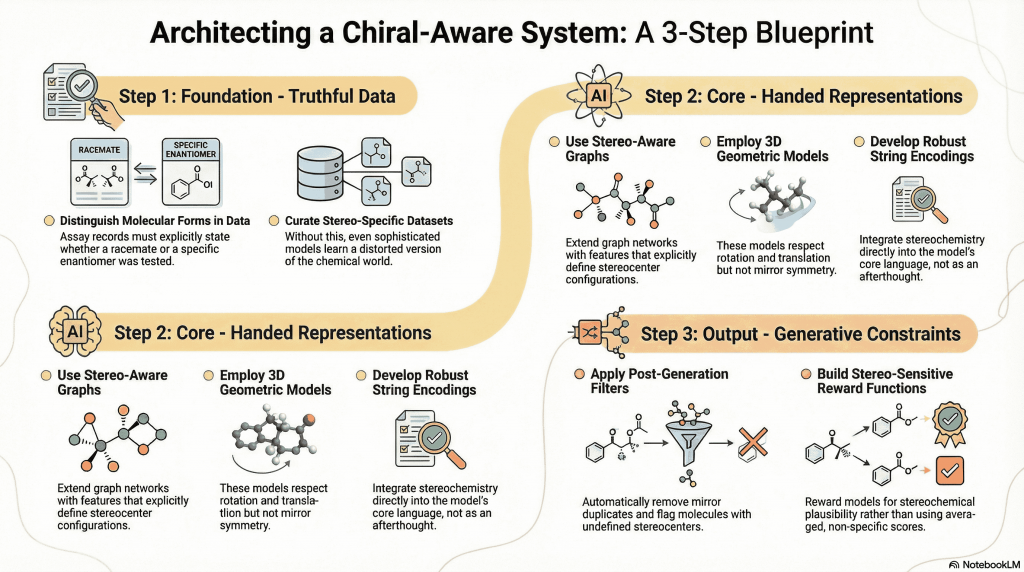

9. Toward Chiral-Aware System

9.1 Data That Tell the Truth

At the foundation, data must distinguish racemates from enantiomers. Assay records should state what form was tested. Key chiral series deserve deliberate, stereo-specific curation. Without this, even the most sophisticated model learns a distorted chemical world.

9.2 Representations That Carry Handedness

Several practical strategies exist:

- Stereo-aware graphs: Extend graph neural networks with explicit features indicating stereocenters and their configurations.

- Geometric models without reflection invariance: Use three-dimensional architectures that respect rotation and translation but not mirror symmetry, allowing enantiomers to map to different internal representations.

- Robust string encodings: Employ grammars that integrate stereochemistry into the core alphabet rather than treating it as optional punctuation.

The principle is simple: if chirality matters chemically, it must matter mathematically.

9.3 Generative Constraints

Post-generation filters can remove mirror duplicates, flag undefined stereocenters, and enforce basic stereochemical plausibility. Reward functions can be built around stereo-sensitive predictors rather than averaged scores.

These steps turn generative models from stereo-sloppy idea machines into tools that respect chemical reality.

10. Human-in-the-Loop Literacy

No technical fix replaces chemical judgment. Chiral literacy in an AI-driven organization means:

- Asking whether models distinguish enantiomers when reviewing predictions.

- Checking top-ranked hits for mirror-image pairs.

- Treating undefined stereochemistry as a data quality issue rather than a cosmetic one.

When these questions become routine, chirality stops being a specialist concern and becomes part of baseline good practice.

Conclusion — Beyond the Blind Spot

AI has changed how chemists explore chemical space. It defines what is visible, plausible, and worth pursuing. That power carries a responsibility: the digital view of chemistry must not erase its three-dimensional nature.

Chiral bias is not a philosophical complaint. It is a concrete consequence of how data are recorded, how molecules are represented, and how models are designed and validated. It shapes hit lists, safety assessments, and notions of novelty.

Teaching machines to see in 3D is therefore more than an engineering challenge. It is a cultural one. It asks teams to treat stereochemistry not as an advanced topic to be layered on later, but as a central feature of molecular understanding—from the dataset to the decision meeting.

Because in drug discovery, missing the mirror can mean missing the molecule.

References

Moores A, Zuin Zeidler VG. Don’t let generative AI shape how we see chemistry. Nat Rev Chem. 2025 Oct;9(10):649-650. doi: 10.1038/s41570-025-00757-9.

Brian Buntz, How stereo-correct data can de-risk AI-driven drug discovery. https://www.drugdiscoverytrends.com/how-stereo-correct-data-can-de-risk-ai-driven-drug-discovery/. News Release: 15 October, 2025

Yasuhiro Yoshikai, Tadahaya Mizuno, Shumpei Nemoto & Hiroyuki Kusuhara. Difficulty in chirality recognition for Transformer architectures learning chemical structures from string representations. Nat Commun 15, 1197, 2024. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-45102-8

Daniel S. Wigh, Jonathan M. Goodman, Alexei A. Lapkin. A review of molecular representation in the age of machine learning. The WIREs Computational Molecular Science, 12, 5, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1603

Derek van Tilborg, Alisa Alenicheva, Francesca Grisoni. Exposing the Limitations of Molecular Machine Learning with Activity Cliffs. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 23, 5938-5951. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.2c01073

Dagmar Stumpfe, Huabin Hu, Jürgen, Bajorath. Evolving Concept of Activity Cliffs. ACS Omega, 4, 11, 14360-14368, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b02221

Ramsundar, B.; Eastman, P.; Walters, P.; Pande, V. Deep Learning for the Life Sciences: Applying Deep Learning to Genomics, Microscopy, Drug Discovery, and More. O’Reilly Media, 2019. ISBN 9781492039839.

Walters WP, Barzilay R. Applications of Deep Learning in Molecule Generation and Molecular Property Prediction. Acc Chem Res. 2021 Jan 19;54(2):263-270. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00699.

Sanchez-Lengeling B, Aspuru-Guzik A. Inverse molecular design using machine learning: Generative models for matter engineering. Science. 2018 Jul 27;361(6400):360-365. doi: 10.1126/science.aat2663.

Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2

Gaiński, P.; Koziarski, M.; Tabor, J.; Śmieja, M. ChiENN: Embracing Molecular Chirality with Graph Neural Networks. In: Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer, 2023; DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-43418-1_3.

Liu, Y.; et al. Interpretable Chirality-Aware Graph Neural Network for Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship Modeling. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2023.

Yan, J.; et al. Interpretable Algorithm Framework of Molecular Chiral Graph Neural Network for QSAR Modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.4c02259.

Ariens EJ. Stereochemistry, a basis for sophisticated nonsense in pharmacokinetics and clinical pharmacology. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 1984 26, 663 to 668.

Kruithof, P.; et al. “Practical aspects of stereochemistry in cheminformatics and molecular modeling.”

Journal of Cheminformatics 2021, 13, 1–26. doi: 10.1186/s13321-021-00519-8

Fourches, D.; Muratov, E.; Tropsha, A. “Trust but verify: on the importance of chemical structure curation in cheminformatics.” J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 1189–1204. doi: 10.1021/ci100176x

Zdrazil B, Felix E, Hunter F, Manners EJ, Blackshaw J, Corbett S, de Veij M, Ioannidis H, Lopez DM, Mosquera JF, Magarinos MP, Bosc N, Arcila R, Kizilören T, Gaulton A, Bento AP, Adasme MF, Monecke P, Landrum GA, Leach AR. The ChEMBL Database in 2023: a drug discovery platform spanning multiple bioactivity data types and time periods. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024 Jan 5;52(D1):D1180-D1192. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad1004.

Schuett KT, Kindermans PJ, Sauceda HE, et al. SchNet: a continuous filter convolutional neural network for modeling quantum interactions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (2017), pp. 992-1002. doi/10.48550/arXiv.1706.08566

Testa B, Trager WF. Drug Metabolism: Chemical and Enzymatic Aspects. CRC Press, 1995.

Tom G, Yu E, Yoshikawa N, Jorner K, Aspuru-Guzik A. Stereochemistry-aware string-based molecular generation. PNAS Nexus. 2025 Oct 14;4(11):pgaf329. doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf329.

Yaëlle Fischer, Thibaud Southiratn, Dhoha Triki, Ruel Cedeno. Deep Learning vs Classical Methods in Potency & ADME Prediction: Insights from a Computational Blind Challenge. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5c01982.

Schneider N, Lewis RA, Fechner N, Ertl P. Chiral Cliffs: Investigating the Influence of Chirality on Binding Affinity. ChemMedChem. 2018 Jul 6;13(13):1315-1324. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201700798.

Husby J, Bottegoni G, Kufareva I, Abagyan R, Cavalli A. Structure-based predictions of activity cliffs. J Chem Inf Model. 2015 May 26;55(5):1062-76. doi: 10.1021/ci500742b.

Further Reading (from chiralpedia blog series – #Chiral Bias in AI Drug Discovery)

- Episode 1: The Promise and the Paradox: AI That Miss the Mirror

- Episode 2: Why Chirality Confuses Machines?

- Episode 3: When Algorithms Miss the Mirror: How Chiral Blind Spots Break the Pipeline?

- Episode 4: Fixing the Bias: Data, Models and Generative Constraints

- Episode 5: Beyond Bias: Toward Chiral Intelligence