“When molecules have two hands but AI only sees one.”

On Visuals and Stereochemical Truth

Some illustrations in this series are generated or assisted by AI to support conceptual understanding. These visuals are intentionally simplified and should not be read as stereochemically rigorous or chemically exact representations. Wherever stereochemical fidelity matters, it is addressed explicitly in the discussion—because in chemistry, especially in chiral systems, intuition must always yield to structure.

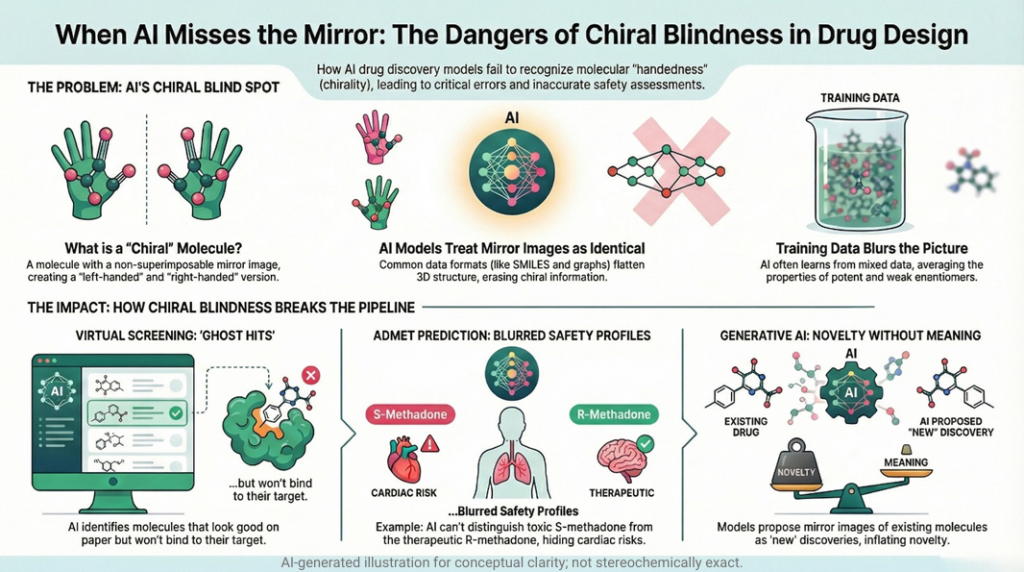

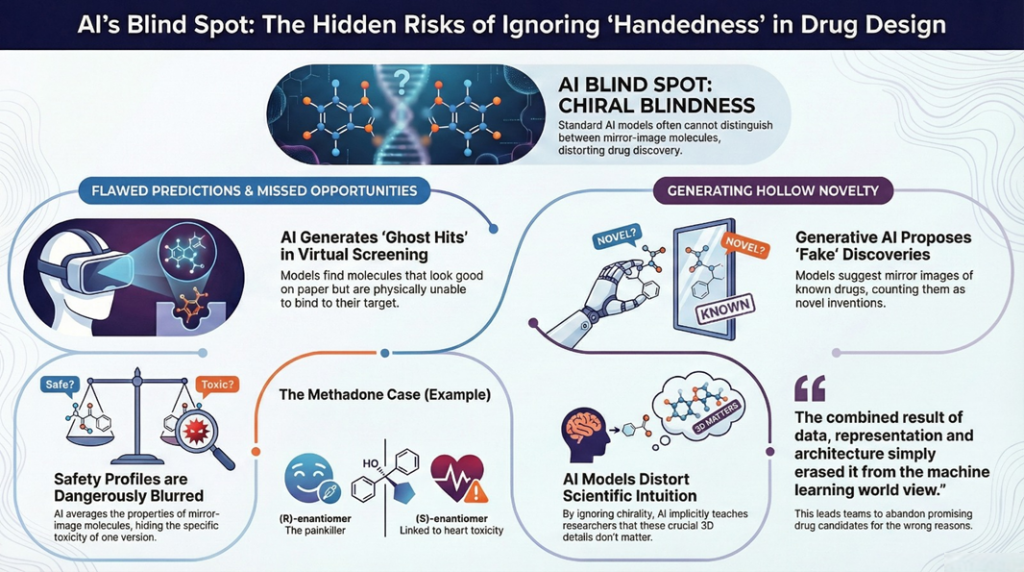

The first two parts of this series looked inside AI systems and showed how stereochemistry gets flattened by SMILES, fingerprints, graphs and some three dimensional models. This part follows the consequences along the drug discovery pipeline. We look at three places where chiral blind spots matter most: virtual screening, ADMET prediction and generative design. We see how models that ignore handedness produce ghost hits, blur toxicity and pharmacokinetic profiles, and inflate novelty with mirror duplicates. Along the way, familiar pharmacology examples such as beta blockers, thalidomide and methadone help anchor the discussion. The claim is simple. Chiral bias is not a theoretical curiosity. It changes which molecules get made and how their risk is perceived.

3.1 Virtual screening: ghost hits and invisible eutomer

Virtual screening is often the first use case for molecular AI in a project. In a ligand based setting you might:

- Train a model on known activity and inactivity for a target.

- Use fingerprints, SMILES or graphs to represent the molecules.

- Score a very large virtual library and pick the top few thousand for more detailed work.

If the input representation hides stereochemistry and the labels mix racemic and enantiopure assays, the model will learn an average picture.

Take propranolol type ligands as an example. The S-enantiomer is the strong beta blocker (eutomer). The R form is much weaker (distomer). If your dataset does not distinguish them, the model only knows that “propranolol like structures are usually active”.

When it sees a new analogue:

- It predicts similar potency for both enantiomers.

- It gives extra credit to racemic structures because the labels used historically reflect the eutomer, but the model has no way to break that tie.

In structure based virtual screening, docking programs generate poses and scoring functions rank them. If the docking step does not enforce stereochemistry correctly, or if the scoring function is not strongly sensitive to subtle three dimensional clashes, both enantiomers can receive similar scores even when visual inspection of the poses shows that one simply does not fit in the pocket.

The result at the level of the hit list is predictable.

- A long tail of mirror image ligands that look good numerically but will never bind properly once synthesized.

- Eutomers that do not stand out as strongly as they should, because the training process has blurred their advantage.

Medicinal chemists then invest time and resources in following up hits that are doomed by construction.

3.2 ADMET: safety profiles blurred by averaging

ADMET models that ignore chirality are even more worrying.

Enantiomers can differ in absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity.

- Only one hand may bind the desired target, but both may bind off targets.

- Only one may be transported efficiently into the CNS.

- One may be metabolized quickly and the other slowly, or via entirely different enzymes.

- Optical isomers can differ in hERG binding, reactive metabolite formation and idiosyncratic toxicity.

If the historical data registers “the drug” without stating whether it was a racemate or an enantiopure formulation, and if the molecular representation throws away stereochemistry, then an ADMET model learns an average profile across both hands.

Methadone is the neat teaching example.

- R methadone is responsible for most of the opioid analgesic effect.

- S methadone is associated with hERG channel block and QT prolongation.

Treating “methadone” as a single entity in a dataset hides this asymmetry. A prediction model cannot distinguish a hypothetical R-isomer only formulation, which might have a better therapeutic index, from the racemic mixture. It also cannot warn clearly if the racemate should be treated as riskier than an R-form only formulation.

The same logic applies to many chiral drugs where one enantiomer is pharmacologically cleaner than the other.

Chiral blind ADMET models lead to risk that is either underestimated or overestimated depending on how the underlying data were mixed. When combined with strong pressure to rely on in silico predictions for early risk assessment, this becomes a systemic problem.

3.3 SAR: cliffs that vanish and smoothness that is fake

Medicinal chemists use structure activity relationships as a map. They look for gradual trends and sharp cliffs. Chiral blind AI distorts both. Cliffs disappear when enantiomers are mapped to the same point in feature space. If flipping a chiral center changes potency by 100 fold, but your features treat R and S as identical, the model cannot reflect that. It must fit a smooth function through conflicting labels and will learn that this part of the scaffold is unimportant.

At the same time, apparent smoothness appears in places where it should not. Labels from racemic and enantiopure assays are blended, so the model learns that activity varies gently with side chain changes even when the true underlying landscape has steep steps between different stereochemical configurations.

This fake smoothness can be seductive. Plots of predicted vs observed activity look fine. General trends make sense. The missing pieces only show up when you realise that the model has learned an averaged world in which left and right hands are the same.

For any program that is thinking about chiral switches, eutomer and distomer, this is particularly dangerous. The models you rely on to support those decisions cannot see the very feature you are trying to exploit.

3.4 Generative AI: novelty without meaning

Generative models are designed to propose new molecules. When chirality is mishandled, that novelty becomes suspect.

Most SMILES based or graph based generative systems that are trained on stereo-sloppy corpora will treat mirror images as separate outputs. They will also generate many structures where stereocenters are unspecified at positions where they clearly should be defined, and occasionally produce molecules that cannot exist as drawn in three dimensions.

Tom and his team found that when a task really depends on getting a molecule’s “handedness” right—like recreating the correct enantiomer or matching its optical fingerprint—any model that ignores stereochemistry struggles and often fails.

This is where the critique by Moores and Zuin Zeidler comes into sharp focus. They argue in Nature Reviews Chemistry that generative AI is starting to shape the way chemists visualise and talk about chemistry. In their examples, large language models generate incorrect reaction schemes and impossible structures that nevertheless look neat and polished. For students and non experts, it is very easy to be impressed by the image and miss the fact that the underlying chemistry is wrong.

The same risk applies to chiral bias.

- If you flood presentations and internal documents with AI generated molecules that scatter chirality randomly or leave it undefined, you implicitly teach that these details are unimportant.

- If you let a generative model propose hundreds of “new” molecules that are mostly mirror images of known scaffolds, your sense of what counts as chemical diversity gets warped.

- If teams forget to ask whether the proposed stereochemistry is synthetically achievable or pharmacologically meaningful, the tool starts to dictate the plausible region of chemical space in a way that is detached from real synthetic and mechanistic constraints.

Generative AI does not just propose molecules. Without careful control, it rewrites the visual and conceptual norms of the discipline.

3.5 A composite beta blocker example

To make this all less abstract, imagine a fictional but realistic beta blocker project.

- The company has historical data on a chiral scaffold where all assays were run on racemates.

- Patents and literature hint that the S enantiomer is far more potent, but there is limited in house enantiopure data.

- They deploy a standard AI stack. That stack includes a GNN trained on racemic data, an ML scoring function on top of docking, and a SMILES based generative model.

Because the GNN does not distinguish R and S, it learns that the scaffold is “moderately active on average”. The docking model gives similar scores to both enantiomers in the binding pocket. The generative model suggests dozens of mirror image analogues as separate ideas.

The chemists then:

- Prioritise a handful of racemic designs that score well in the models.

- See modest potency in vitro because the distomer dilutes the effect of the eutomer.

- Conclude that the series is unpromising and move on.

At no point did anyone deliberately ignore chirality. The combined result of data, representation and architecture simply erased it from the machine learning world view. The real opportunity, an enantiopure S-series, never gets the attention it deserves.

3.6 Scale makes the problem worse

If only one individual project team made these mistakes, the damage would be limited. AI changes the scale.

When the same stereo-blind models are rolled out across many projects and portfolios, the bias becomes an institutional pattern.

- Pipelines that treat “compound X” as a single object when in reality there are several stereochemical forms.

- Corporate memory that reflects averaged behaviour instead of specific enantiomer profiles.

- A gradual drift in intuition where chemically naive team members assume that if the model does not care about chirality here, it must not matter.

This is how a technical modelling issue arrives at strategic decisions.

3.7 Looking ahead

By this point the problem should be clear from multiple angles. Models that ignore chirality produce the wrong hit lists, blur safety assessments and fill design spaces with hollow novelty.

Episode 4 will concentrate on concrete remedies. It will cover data curation practices that clean up stereochemistry, model architectures and feature schemes that make chirality visible to the network, and constraints on generative AI so that it respects mirrors instead of abusing them. It will also bring the Moores and Zuin Zeidler warning back in as a design principle rather than just a cautionary quote.

References

Moores A, Zuin Zeidler VG. Don’t let generative AI shape how we see chemistry. Nat Rev Chem. 2025 Oct;9(10):649-650. doi: 10.1038/s41570-025-00757-9.

Tom G, Yu E, Yoshikawa N, Jorner K, Aspuru-Guzik A. Stereochemistry-aware string-based molecular generation. PNAS Nexus. 2025 Oct 14;4(11):pgaf329. doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf329.

Brian Buntz, How stereo-correct data can de-risk AI-driven drug discovery. https://www.drugdiscoverytrends.com/how-stereo-correct-data-can-de-risk-ai-driven-drug-discovery/. News Release: 15 October, 2025

Yasuhiro Yoshikai, Tadahaya Mizuno, Shumpei Nemoto & Hiroyuki Kusuhara. Difficulty in chirality recognition for Transformer architectures learning chemical structures from string representations. Nat Commun 15, 1197, 2024. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-45102-8

Daniel S. Wigh, Jonathan M. Goodman, Alexei A. Lapkin. A review of molecular representation in the age of machine learning. The WIREs Computational Molecular Science, 12, 5, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1603

Derek van Tilborg, Alisa Alenicheva, Francesca Grisoni. Exposing the Limitations of Molecular Machine Learning with Activity Cliffs. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 23, 5938-5951. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.2c01073

Dagmar Stumpfe, Huabin Hu, Jürgen, Bajorath. Evolving Concept of Activity Cliffs. ACS Omega, 4, 11, 14360-14368, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b02221

Ramsundar, B.; Eastman, P.; Walters, P.; Pande, V. Deep Learning for the Life Sciences: Applying Deep Learning to Genomics, Microscopy, Drug Discovery, and More. O’Reilly Media, 2019. ISBN 9781492039839.

Walters WP, Barzilay R. Applications of Deep Learning in Molecule Generation and Molecular Property Prediction. Acc Chem Res. 2021 Jan 19;54(2):263-270. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00699.

Sanchez-Lengeling B, Aspuru-Guzik A. Inverse molecular design using machine learning: Generative models for matter engineering. Science. 2018 Jul 27;361(6400):360-365. doi: 10.1126/science.aat2663.

Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2

Gaiński, P.; Koziarski, M.; Tabor, J.; Śmieja, M. ChiENN: Embracing Molecular Chirality with Graph Neural Networks. In: Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer, 2023; DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-43418-1_3.

Liu, Y.; et al. Interpretable Chirality-Aware Graph Neural Network for Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship Modeling. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2023.

Yan, J.; et al. Interpretable Algorithm Framework of Molecular Chiral Graph Neural Network for QSAR Modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.4c02259.

Ariens EJ. Stereochemistry, a basis for sophisticated nonsense in pharmacokinetics and clinical pharmacology. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 1984 26, 663 to 668.

Kruithof, P.; et al. “Practical aspects of stereochemistry in cheminformatics and molecular modeling.”

Journal of Cheminformatics 2021, 13, 1–26. doi: 10.1186/s13321-021-00519-8

Fourches, D.; Muratov, E.; Tropsha, A. “Trust but verify: on the importance of chemical structure curation in cheminformatics.” J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 1189–1204. doi: 10.1021/ci100176x

Zdrazil B, Felix E, Hunter F, Manners EJ, Blackshaw J, Corbett S, de Veij M, Ioannidis H, Lopez DM, Mosquera JF, Magarinos MP, Bosc N, Arcila R, Kizilören T, Gaulton A, Bento AP, Adasme MF, Monecke P, Landrum GA, Leach AR. The ChEMBL Database in 2023: a drug discovery platform spanning multiple bioactivity data types and time periods. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024 Jan 5;52(D1):D1180-D1192. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad1004.

Schuett KT, Kindermans PJ, Sauceda HE, et al. SchNet: a continuous filter convolutional neural network for modeling quantum interactions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (2017), pp. 992-1002. doi/10.48550/arXiv.1706.08566

Testa B, Trager WF. Drug Metabolism: Chemical and Enzymatic Aspects. CRC Press, 1995.

Yaëlle Fischer, Thibaud Southiratn, Dhoha Triki, Ruel Cedeno. Deep Learning vs Classical Methods in Potency & ADME Prediction: Insights from a Computational Blind Challenge. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5c01982.

Schneider N, Lewis RA, Fechner N, Ertl P. Chiral Cliffs: Investigating the Influence of Chirality on Binding Affinity. ChemMedChem. 2018 Jul 6;13(13):1315-1324. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201700798.

Husby J, Bottegoni G, Kufareva I, Abagyan R, Cavalli A. Structure-based predictions of activity cliffs. J Chem Inf Model. 2015 May 26;55(5):1062-76. doi: 10.1021/ci500742b.

Krantz MJ, et al. QTc interval screening in methadone treatment. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009 150, 387 to 395.

Stokes JM, Yang K, Swanson K, et al., A Deep Learning Approach to Antibiotic Discovery. Cell. 2020 Feb 20;180(4):688-702.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.021. Erratum in: Cell. 2020 Apr 16;181(2):475-483. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.001.