“AI isn’t blind—just stereo-sloppy”

On Visuals and Stereochemical Truth

Some illustrations in this series are generated or assisted by AI to support conceptual understanding. These visuals are intentionally simplified and should not be read as stereochemically rigorous or chemically exact representations. Wherever stereochemical fidelity matters, it is addressed explicitly in the discussion—because in chemistry, especially in chiral systems, intuition must always yield to structure.

The first episode argued that many AI models in drug discovery are effectively blind to molecular handedness. This one explains why in more detail. We look at how molecules are encoded as SMILES strings, fingerprints, two dimensional graphs and three dimensional coordinates. At each stage we identify where stereochemical information is lost or blurred. Then we look at common architectures, especially graph neural networks, SMILES Transformers and geometric deep learning models, and explain why many of them are reflection invariant by design. The result is slightly ironic. The models are doing exactly what we asked them to do. The mistake lies in the question we posed.

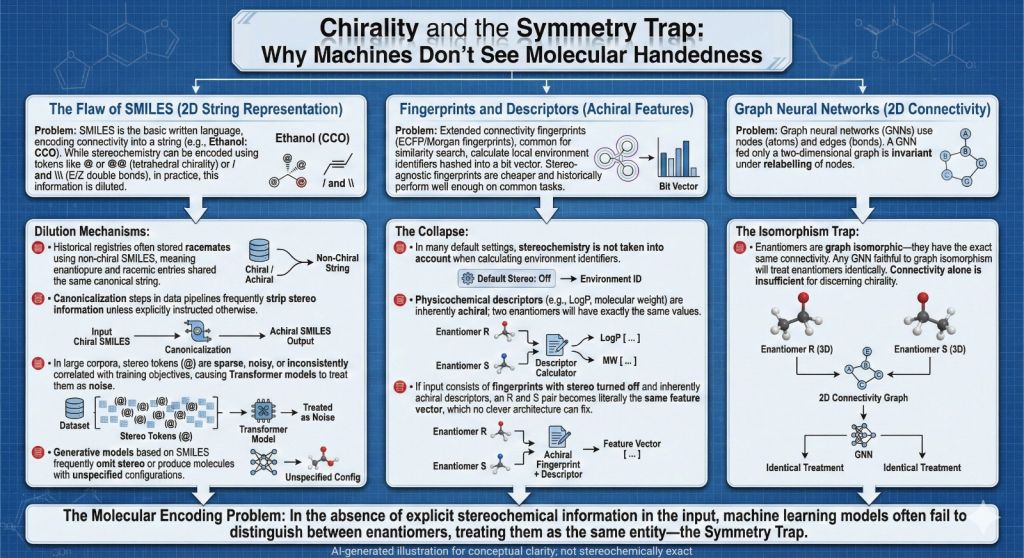

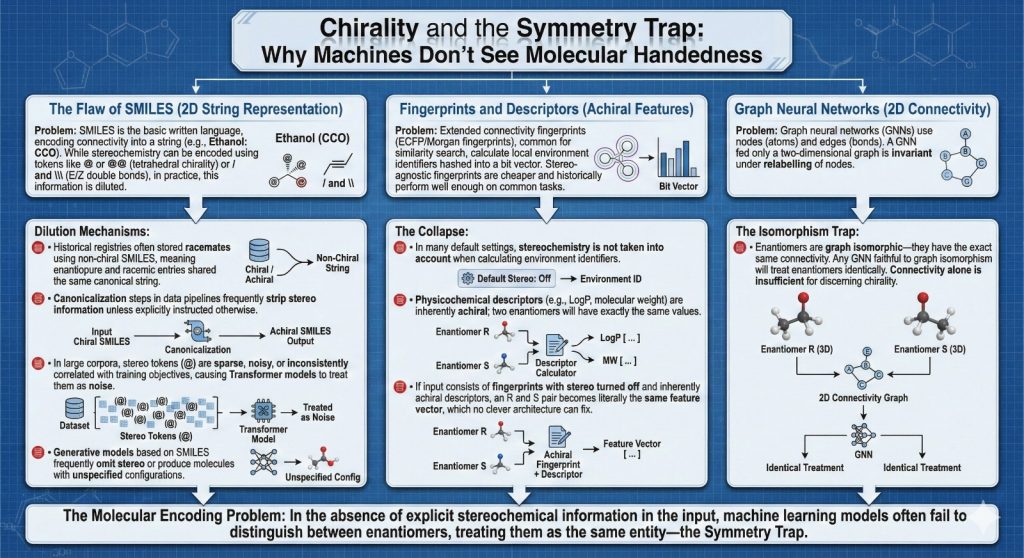

2.1 SMILES as a language that mostly forgets 3D

SMILES has been the basic written language of cheminformatics for decades. It turns connectivity into a string, for example:

- Ethanol: CCO

- Aspirin: CC(=O)OC1=CC=CC=C1C(=O)O

Tetrahedral chirality appears as @ or @@ and E or Z double bonds use slash or backslash. In theory this is enough to encode full stereochemistry.

In practice several things dilute that information.

- Many historical registries stored racemates with a non chiral SMILES. Enantiopure entries and racemic entries share the same canonical string.

- Canonicalization steps in data pipelines sometimes strip stereo unless explicitly told to keep it.

- In large corpora, the stereo tokens are sparse and noisy. When a Transformer model learns to read SMILES as a language, it focuses on the most frequent and predictive patterns. If @ is rare, inconsistent or weakly correlated with the training objectives, it will often be treated as noise.

When you evaluate these models on tasks that do not depend on stereochemistry, they look good. When you construct tasks where enantiomers differ strongly in the property of interest, their limitations become obvious.

Generative models based on SMILES show another symptom. They generate valid strings, but:

- Frequently omit stereo where it matters.

- Produce molecules where chiral centers are present but configuration is unspecified.

- Rediscover known molecules with scrambled stereocenters.

On a static benchmark that does not check stereo, all looks well. A chemist who inspects the results by hand often sees a tidy pile of broken three dimensional chemistry.

2.2 Fingerprints and descriptors that ignore handedness

Extended connectivity fingerprints, such as ECFP or Morgan fingerprints, are among the most common molecular features in QSAR and similarity search. They work roughly as follows.

- Start from each atom.

- Expand out to a certain radius, building local environment identifiers.

- Hash these into a bit vector.

Stereochemistry can be taken into account when calculating the environment identifiers. In many default settings, it is not. The reasons are historical and pragmatic. Stereo agnostic fingerprints are cheaper to compute and often perform well enough on common tasks. Physicochemical descriptors behave similarly. LogP, molecular weight, TPSA and many standard counts do not see handedness. Two enantiomers have exactly the same values.

If the input to a model consists of:

- Fingerprints with stereo turned off, and

- Physicochemical descriptors that are inherently achiral,

then an R and S pair becomes literally the same feature vector. No amount of clever architecture on top can fix that.

2.3 Graph neural networks and the symmetry trap

Graph neural networks try to work closer to the actual structure. The basic recipe is straightforward [4].

- Atoms become nodes with features such as atomic number, formal charge and hybridization.

- Bonds become edges with features such as bond order and aromaticity.

- Messages are passed between nodes along edges for several iterations, producing a final embedding.

If all you provide is a two dimensional graph, you get a nice property. The network is invariant under relabelling of nodes. It does not care how you order the atoms, only how they are connected.

Enantiomers are graph isomorphic. They have the same connectivity. Their adjacency matrices differ only by permutation. That means that any GNN that is faithful to graph isomorphism will treat them identically unless you add extra features to break the symmetry. On vanilla two dimensional graphs, there is simply no way to tell left hand from right hand.

Zhou and co workers tested this explicitly. They created tasks where enantiomers have different labels and asked GNNs to predict them. Standard architectures failed. When they added stereo aware node features or three dimensional coordinates, performance improved.

The takeaway is clear. Graphs are powerful, but connectivity alone is not enough if you care about chirality.

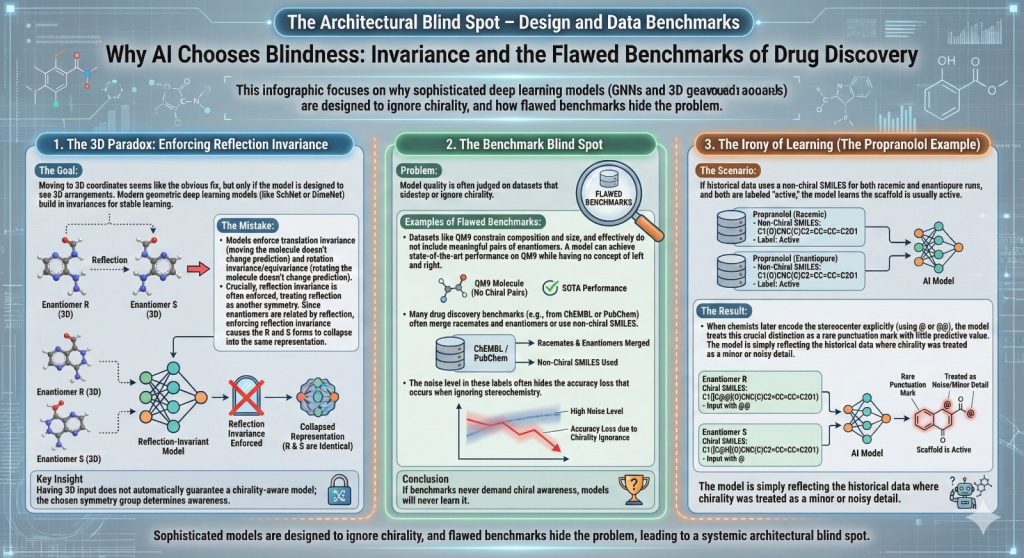

2.4 Three dimensional models that throw away the mirror

Moving to three dimensional models feels like the obvious fix. If you give a network full coordinates, surely it can see three dimensional arrangements. It can, but only if you design it to.

Modern geometric deep learning models such as SchNet, DimeNet and SE(3) equivariant networks often build in invariances to make learning stable and data efficient.

- Translation invariance. Moving the whole molecule in space should not change the prediction.

- Rotation invariance or equivariance. Rotating the molecule should not change the prediction, or at least the prediction should transform in a predictable way.

- Sometimes reflection invariance is also enforced. Reflecting the coordinates through a plane is treated like another symmetry.

Enantiomers are related by reflection. If you insist that your model is invariant under reflection, then the R and S forms collapse into the same representation. That is exactly what you do not want if your property of interest is enantioselective binding, chiral catalysis or anything else that depends strongly on handedness.

Some newer models and variants avoid this by being equivariant to rotations but not to reflections, and by including features that are sensitive to orientation such as signed volumes. The important point is that “three dimensional input” does not automatically imply “chirality aware model”. You have to choose the symmetry group you respect.

2.5 Benchmarks that never ask about chirality

The other half of the story is how we judge model quality.

Datasets like QM9 have been essential for testing geometric models. They contain small organic molecules with quantum chemical properties. They also sidestep chirality.

- QM9 constrains composition and size.

- It effectively does not include meaningful pairs of enantiomers.

- Each connectivity appears once.

A model can reach state of the art performance on QM9 and still have no concept of left and right in molecular space.

Many drug discovery benchmarks have similar issues. Activity data from ChEMBL or PubChem often merge racemates and enantiomers, or use non chiral SMILES. A model that ignores stereochemistry may lose a small amount of accuracy on some tasks, but the noise level in the labels hides the problem.

Tom and collaborators tackled this head on. They proposed stereochemistry aware string based generative models and tested them on tasks where chirality matters, such as rediscovering a specific enantiomer or optimizing circular dichroism spectra. In those settings, stereo agnostic baselines struggled, even when they looked fine on more generic tasks.

If your benchmarks never demand chiral awareness, your models will never learn it.

2.6 A simple thought experiment with propranolol as SMILES

Consider propranolol again. Imagine that your historical data uses a non chiral SMILES for both the racemate and for some enantiopure runs. The labels tell you “active” but do not distinguish which form was used in which assay.

You now fine tune a SMILES based Transformer on this. It happily learns that the propranolol scaffold is usually active and that details around the chiral center do not matter.

Later, someone decides to start encoding the stereocenter explicitly with @ or @@. From the chemist’s point of view, this is a crucial distinction. From the model’s point of view, you just added a rare punctuation mark that has little predictive value based on its training history. The model is not ignorant in general. It is simply reflecting the fact that, in the data it saw, chirality was treated as a minor or noisy detail.

2.7 Looking ahead

So far the series has stayed fairly close to the technical plumbing. We have looked at how different representations and architectures flatten three dimensional reality into forms that erase chirality or confuse machine.

The next step is to see what this does to actual drug discovery work.

Episode 3 follows this blind spot through three domains that matter in practice: virtual screening, ADMET prediction and generative design. It shows how ghost hits, blurred toxicity profiles and useless novelty arise from the same underlying problem.

References

Moores A, Zuin Zeidler VG. Don’t let generative AI shape how we see chemistry. Nat Rev Chem. 2025 Oct;9(10):649-650. doi: 10.1038/s41570-025-00757-9.

Tom G, et al. Stereochemistry aware string based molecular generation. PNAS Nexus. 2025 4, pgaf329. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf329

Weininger D. SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1988, 28, 1, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci00057a005

Brian Buntz, How stereo-correct data can de-risk AI-driven drug discovery. https://www.drugdiscoverytrends.com/how-stereo-correct-data-can-de-risk-ai-driven-drug-discovery/. News Release: 15 October, 2025

Yasuhiro Yoshikai, Tadahaya Mizuno, Shumpei Nemoto & Hiroyuki Kusuhara. Difficulty in chirality recognition for Transformer architectures learning chemical structures from string representations. Nat Commun 15, 1197, 2024. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-45102-8

Daniel S. Wigh, Jonathan M. Goodman, Alexei A. Lapkin. A review of molecular representation in the age of machine learning. The WIREs Computational Molecular Science, 12, 5, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1603

Derek van Tilborg, Alisa Alenicheva, Francesca Grisoni. Exposing the Limitations of Molecular Machine Learning with Activity Cliffs. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 23, 5938-5951. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.2c01073

Dagmar Stumpfe, Huabin Hu, Jürgen, Bajorath. Evolving Concept of Activity Cliffs. ACS Omega, 4, 11, 14360-14368, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b02221

Ramsundar, B.; Eastman, P.; Walters, P.; Pande, V. Deep Learning for the Life Sciences: Applying Deep Learning to Genomics, Microscopy, Drug Discovery, and More. O’Reilly Media, 2019. ISBN 9781492039839.

Walters WP, Barzilay R. Applications of Deep Learning in Molecule Generation and Molecular Property Prediction. Acc Chem Res. 2021 Jan 19;54(2):263-270. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00699.

Rogers D, Hahn M. Extended connectivity fingerprints. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 2010 50, 742 to 754. doi: 10.1021/ci100050t.

Gasteiger J, Engel T, editors. Chemoinformatics: A Textbook. Wiley VCH, 2003.

Gilmer J, Schoenholz SS, Riley PF, Vinyals O, Dahl GE. Neural message passing for quantum chemistry. Proceedings of ICML 2017. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1704.01212

Gaiński, P.; Koziarski, M.; Tabor, J.; Śmieja, M. ChiENN: Embracing Molecular Chirality with Graph Neural Networks. In: Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer, 2023; doi:10.1007/978-3-031-43418-1_3.

Liu, Y.; et al. Interpretable Chirality-Aware Graph Neural Network for Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship Modeling. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2023.

Yan, J.; et al. Interpretable Algorithm Framework of Molecular Chiral Graph Neural Network for QSAR Modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jcim.4c02259.

Krenn M, Haese F, Nigam AK, Friederich P, Aspuru Guzik A. Self referencing embedded strings SELFIES: a 100 percent robust molecular string representation. Machine Learning: Science and Technology. 2020 1, 045024. doi: 10.1088/2632-2153/aba947

Ramakrishnan, R., Dral, P., Rupp, M. et al. Quantum chemistry structures and properties of 134 kilo molecules. Sci Data 1, 140022 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2014.22

Kruithof, P.; et al. “Practical aspects of stereochemistry in cheminformatics and molecular modeling.”

Journal of Cheminformatics 2021, 13, 1–26. DOI: 10.1186/s13321-021-00519-8

Fourches, D.; Muratov, E.; Tropsha, A. “Trust but verify: on the importance of chemical structure curation in cheminformatics.” J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 1189–1204. DOI: 10.1021/ci100176x

Schuett KT, Kindermans PJ, Sauceda HE, et al. SchNet: a continuous filter convolutional neural network for modeling quantum interactions. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2018 14, 6632 to 6642.

Bronstein MM, Bruna J, LeCun Y, Szlam A, Vandergheynst P. Geometric deep learning: grids, groups, graphs, geodesics and gauges. Nature Reviews Machine Intelligence. 2021 2, 743 to 755. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2104.13478.

| Bai Q, Xu T, Huang J, Pérez-Sánchez H. Geometric deep learning methods and applications in 3D structure-based drug design. Drug Discov Today. 2024 Jul;29(7):104024. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2024.104024. |

Brian Buntz, How stereo-correct data can de-risk AI-driven drug discovery, 2025. https://www.drugdiscoverytrends.com/how-stereo-correct-data-can-de-risk-ai-driven-drug-discovery/

Yaëlle Fischer, Thibaud Southiratn, Dhoha Triki, Ruel Cedeno. Deep Learning vs Classical Methods in Potency & ADME Prediction: Insights from a Computational Blind Challenge. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.5c01982.

Schneider N, Lewis RA, Fechner N, Ertl P. Chiral Cliffs: Investigating the Influence of Chirality on Binding Affinity. ChemMedChem. 2018 Jul 6;13(13):1315-1324. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201700798.

Husby J, Bottegoni G, Kufareva I, Abagyan R, Cavalli A. Structure-based predictions of activity cliffs. J Chem Inf Model. 2015 May 26;55(5):1062-76. doi: 10.1021/ci500742b.