Lead

Chiral resolution, the process of separating enantiomers, is crucial in various fields such as pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and food industries. Chirality, as discussed in previous sections, involves molecules that are mirror images of each other but cannot be superimposed. This seemingly subtle difference leads to enantiomers having different biological, chemical, and pharmacological properties. The importance of chiral resolution has increased, especially in pharmaceutical industries, where the efficacy and safety of drugs can vary dramatically between enantiomers.

1. Overview of Traditional Chiral Separation Methods

Chiral separation methods have evolved over the years, moving from traditional techniques like crystallization to more sophisticated approaches such as chromatography and supercritical fluid separation. The classic techniques rely on creating a chiral environment where one enantiomer interacts more favorably, allowing for its separation. The earliest and simplest method of chiral separation is crystallization, where diastereomers, often formed by adding a chiral agent, are separated based on their different solubility properties (Sui, 2023). Chromatographic techniques, which have seen significant advancements over the past few decades, use chiral stationary phases (CSPs) or chiral additives to differentiate between enantiomers based on their interaction with the chiral environment. Other methods, such as membrane separation and kinetic resolution, have also gained attention for their efficiency and ability to handle complex mixtures.

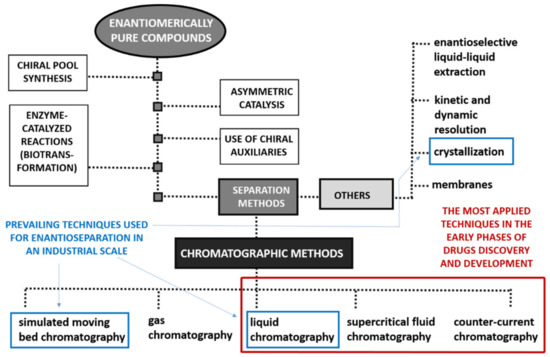

In response to the surge in medicinal chemistry research focused on creating new biologically active compounds in enantiomerically pure forms, and in line with stricter regulatory requirements for patenting new chiral drugs, developing methods for enantioselective production and evaluating enantiomeric purity has become essential. Consequently, various enantioselective synthetic methodologies and diverse analytical and preparative techniques have been developed. Despite this, pure enantiomers can be obtained through several methods, as shown in Figure below.

Methods for obtaining enantiopure compounds

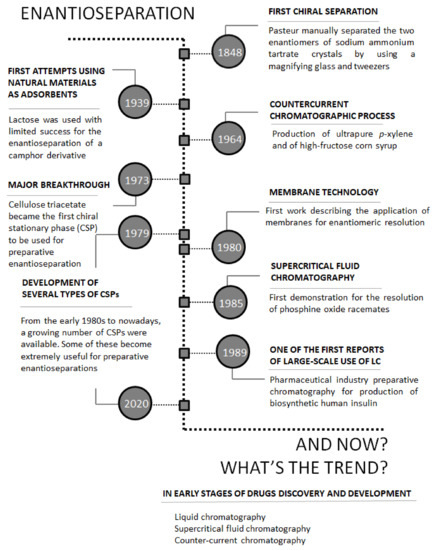

From a medicinal Chemistry perspective, separating enantiomers on a preparative scale is incredibly important. The Figure below highlights some of the key milestones in enantioseparation.

Chronology of key milestones in enantioseparation

2. The Importance of Efficient Separation

Efficient chiral separation is essential because the two enantiomers of a compound often exhibit different behaviors when interacting with biological systems. In some cases, one enantiomer may be therapeutically active while the other may be inactive or even harmful. Therefore, separating the desired enantiomer to achieve a high level of purity is critical in drug manufacturing. For example, the R-enantiomer of thalidomide is sedative, while the S-enantiomer is teratogenic, illustrating the necessity of precise chiral resolution.

Moreover, the efficiency of a chiral separation technique can significantly affect the production cost and scalability of pharmaceuticals. Techniques such as chromatography and crystallization, when applied correctly, can minimize waste, improve product yield, and enhance the overall safety and efficacy of drugs.

3. Chromatography in Chiral Resolution

Types of Chromatography: HPLC, GC, SFC

Chromatography is one of the most widely used methods for chiral resolution. The primary types of chromatography utilized in separating enantiomers are high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), gas chromatography (GC), and supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC). Each technique has its own advantages and specific applications.

- HPLC is the most common form of chromatography for chiral separation. It uses a liquid mobile phase and a chiral stationary phase (CSP) to separate enantiomers based on their interaction with the stationary phase. HPLC is particularly effective for resolving enantiomers of complex, non-volatile, and thermally unstable compounds, making it ideal for pharmaceutical applications.

- GC, in contrast, uses a gas as the mobile phase. It is suitable for the separation of volatile and thermally stable compounds. GC has high resolution and speed, but its application in chiral resolution is limited by the volatility of the analytes.

- SFC combines elements of both HPLC and GC, using supercritical CO₂ as the mobile phase. SFC is gaining popularity in industrial settings because it is faster than HPLC and more environmentally friendly due to reduced solvent usage.

- SMB SMB (Simulated Moving Bed) technology comes from chromatographic separation techniques. It works by exploiting the differences in how components partition between a mobile phase and a stationary phase. Essentially, the mobile phase flows through a column packed with the stationary phase, allowing the mixture to be separated based on these differences. Small scale SMB units constitute a useful tool for the pharmaceutical industry.

Chiral Chromatographic separation: Strategy and Approaches

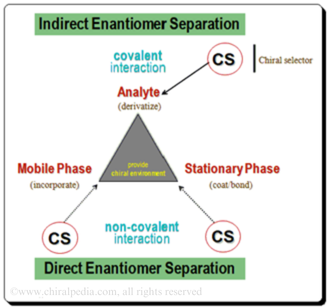

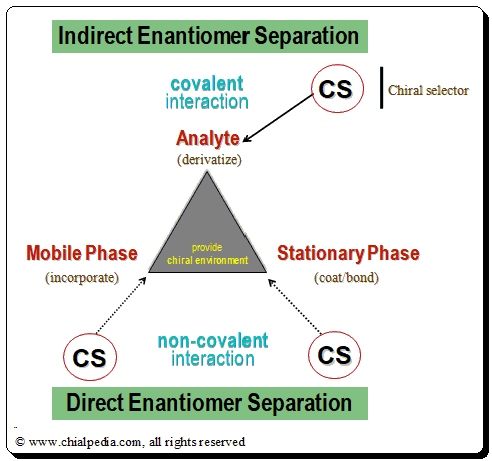

The three variables available in chromatographic system viz. Analyte, Stationary Phase and Mobile Phase, are made to interact with a chiral auxiliary (chiral selector, CS) whereby it forms a diastereomeric complex which has different physicochemical properties and makes it possible to separate the enantiomers. Based on the nature of the diastereomeric complex formed between the CS-CA species, enantiomer separation mythologies are categorized into approaches: Indirect and direct enantiomer separation mode.

For more information on “Chiral Chromatographic separation: Strategy and Approaches” access the following article <https://chiralpedia.com/blog/chiral-hplc-separation-strategy-and-approaches/>

Mechanisms of Enantiomer Separation in Chromatography

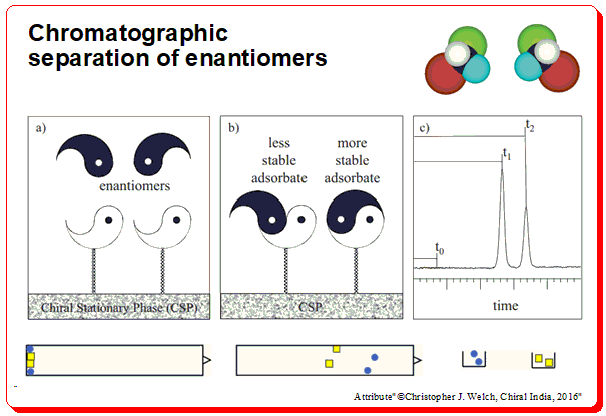

The separation of enantiomers in chromatographic techniques relies on the interaction between the enantiomers and a chiral environment created by the chiral stationary phase (CSP) or chiral additives in the mobile phase. CSPs are designed to selectively interact with one enantiomer over the other, resulting in different retention times for each enantiomer.

In HPLC, for example, the enantiomers pass through a column packed with CSP, where one enantiomer forms transient diastereomeric complexes with the stationary phase, leading to a longer retention time compared to the other enantiomer. The key to successful chiral separation is choosing the appropriate CSP, which can include cyclodextrins, crown ethers, or macrocyclic antibiotics that are tailored to specific enantiomers. Consult the following article for more in formation on the mechanism chromatographic separation <https://chiralpedia.com/blog/direct-enantiomer-separation-by-hplc/>.

In SFC, the low viscosity and high diffusivity of the supercritical CO₂ mobile phase allow for high-speed separations. Additionally, the use of CO₂ as the mobile phase reduces the need for large amounts of organic solvents, making SFC a greener alternative to traditional chromatography.

Use of Chiral Stationary Phases (CSPs)

Chiral stationary phases (CSPs) are essential components in chiral chromatography, providing the chiral environment necessary for the separation of enantiomers. CSPs work by selectively interacting with one enantiomer over the other, leading to differences in their retention times and enabling their separation.

The choice of CSP depends on the chemical nature of the enantiomers being separated. Common CSPs include polysaccharide-based materials, such as cellulose and amylose derivatives, which are widely used due to their versatility and ability to separate a broad range of enantiomers. Cyclodextrins and crown ethers are also popular due to their ability to form inclusion complexes with enantiomers, enhancing selectivity.

Case Study: HPLC for Resolving Racemic Drug Mixtures

One practical application of HPLC in chiral resolution is the separation of racemic mixtures in drug development. A prominent example is the use of HPLC to resolve the enantiomers of the drug ibuprofen. As previously mentioned, the S-enantiomer of ibuprofen is responsible for its anti-inflammatory effects, while the R-enantiomer is inactive. By using an HPLC system with a chiral stationary phase, pharmaceutical companies can isolate the active S-enantiomer, thereby increasing the efficacy of the drug and reducing potential side effects.

HPLC has also been used to resolve the enantiomers of β-blockers such as propranolol, where the S-enantiomer has greater efficacy in blocking beta-adrenergic receptors compared to the R-enantiomer. This ability to separate enantiomers efficiently makes HPLC an invaluable tool in the pharmaceutical industry, ensuring that drugs are not only effective but also safe for human consumption (Sui, 2023).

4. Crystallization Techniques in Chiral Resolution

Basic Principles of Crystallization-Based Methods

Crystallization-based methods are among the oldest techniques used for chiral resolution. These methods rely on the fact that enantiomers can form different crystalline structures when crystallized under the right conditions. One enantiomer may crystallize out of a solution, leaving the other in the liquid phase. This process is known as diastereomeric crystallization when a chiral resolving agent is used to form diastereomeric salts with the racemic mixture, which have different solubility properties.

The key to successful crystallization lies in the careful selection of solvents and crystallization conditions. The process can be optimized by varying parameters such as temperature, concentration, and the choice of the resolving agent, which influences the formation of crystals with the desired enantiomer.

Salt-Forming Crystal Resolution: Theory and Application

Salt-forming crystallization is a popular method for separating enantiomers, particularly in large-scale pharmaceutical production. This technique involves the addition of a resolving agent to a racemic mixture to form diastereomeric salts, which have different solubility properties and can be separated through crystallization.

For example, racemic acids can be separated using chiral bases such as brucine or quinine to form salts with one enantiomer. These salts are then crystallized, and the diastereomers can be separated based on their different solubilities in a particular solvent. After separation, the pure enantiomer can be recovered by breaking the salt and removing the resolving agent.

Pasteur’s Classic Stereoisomer Separation Experiment

The earliest example of crystallization-based chiral resolution is Louis Pasteur’s groundbreaking experiment in 1848. Pasteur observed that crystals of sodium ammonium tartrate formed two distinct shapes, which he separated manually using tweezers. By dissolving the crystals in water, he found that one set of crystals rotated polarized light to the right, while the other rotated light to the left, confirming that the two forms were enantiomers.

Pasteur’s experiment was the first demonstration of the existence of enantiomers and laid the foundation for the development of chiral resolution techniques. His work remains a cornerstone in the field of stereochemistry and continues to inspire modern methods of chiral separation.

Advances in Modern Crystallization for Large-Scale Production

While Pasteur’s method was groundbreaking, it was far from practical for industrial applications. Modern advances in crystallization techniques have enabled large-scale production of enantiopure compounds, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry. One of the most notable advances is the development of eutectic crystallization, which allows for the efficient separation of enantiomers by forming eutectic mixtures that crystallize selectively.

Another recent innovation is the use of continuous crystallization processes, which offer better control over the crystallization environment and enable the production of enantiopure compounds on an industrial scale. These methods have significantly improved the efficiency and scalability of crystallization-based chiral resolution, making them viable for large-scale pharmaceutical production.

Comparison of Methods

Efficiency, Cost, and Scalability of Chromatography vs Crystallization

When comparing chromatography and crystallization techniques for chiral resolution, several factors come into play, including efficiency, cost, and scalability. Chromatography, particularly HPLC and SFC, offers high-resolution separation of enantiomers with relatively high throughput, making it suitable for small to medium-scale applications in research and drug development. However, chromatography can be costly due to the need for specialized columns, solvents, and equipment.

Crystallization, on the other hand, is a much more cost-effective method for large-scale chiral separation. While the initial development of crystallization conditions can be time-consuming, once optimized, crystallization offers a highly scalable solution for producing enantiopure compounds in bulk. For example, salt-forming crystallization is widely used in the pharmaceutical industry for producing large quantities of enantiopure drugs.

Advantages and Limitations of Each Technique

The advantages of chromatography lie in its versatility and precision. Chromatography can be applied to a wide range of compounds, including those that are thermally unstable or non-volatile. It also offers high resolution and the ability to separate complex mixtures. However, the main limitations are cost and scalability, particularly for industrial applications where large quantities of enantiopure compounds are required.

Crystallization, on the other hand, excels in large-scale production and cost efficiency. Once the crystallization conditions have been optimized, it can produce enantiopure compounds in bulk with relatively low operational costs. The main limitation of crystallization is its applicability to certain types of compounds, as not all enantiomers can be efficiently separated using this method. Additionally, crystallization often requires extensive optimization of conditions, which can be time-consuming.

Conclusion

Choosing the Right Method for Specific Applications

Choosing the appropriate chiral resolution technique depends on the specific requirements of the application. For small-scale research and drug development, chromatography offers the precision and versatility needed to separate a wide range of enantiomers. However, for large-scale production, crystallization methods, particularly salt-forming crystallization, provide a more cost-effective and scalable solution.

In many cases, a combination of techniques may be used. For example, HPLC might be employed to screen for the best crystallization conditions, allowing for the development of an efficient crystallization process for industrial-scale production. As the field of chiral resolution continues to evolve, new methods such as supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) and continuous crystallization are likely to play an increasingly important role in meeting the demands of the pharmaceutical and chemical industries.

Further Reading

Pinto, M.M.M.; Fernandes, C.; Tiritan, M.E. (2020). Chiral Separations in Preparative Scale: A Medicinal Chemistry Point of View. Molecules, 25, 1931. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25081931

Hangh, X. (2024). Advancement of Chiral Resolution and Separations: Techniques and Applications. Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology, GTREE 2023, Volume 83, pp. 305-310.

Sui, H. (2023). Strategies for Chiral Separation: From Racemate to Enantiomer. RSC Publishing.

Suliman, A. (2023). Emerging Developments in Separation Techniques and Analysis of Chiral Pharmaceuticals. Molecules.

Malacarne, F. (2024). Unconventional Approaches for Chiral Resolution. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry.

Fernandes, C.; Tiritan, M.E.; Pinto, M.M.M. (2017). Chiral Separation in Preparative Scale: A Brief Overview of Membranes as Tools for Enantiomeric Separation. Symmetry, 9, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym9100206

Luı́s S. Pais, José M. Loureiro, Alı́rio E. Rodrigues, Chiral separation by SMB chromatography,

Separation and Purification Technology, 20, 67-77, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1383-5866(00)00063-0