“When algorithms forget the mirror, molecules lose their meaning”

On Visuals and Stereochemical Truth

Some illustrations in this series are generated or assisted by AI to support conceptual understanding. These visuals are intentionally simplified and should not be read as stereochemically rigorous or chemically exact representations. Wherever stereochemical fidelity matters, it is addressed explicitly in the discussion—because in chemistry, especially in chiral systems, intuition must always yield to structure.

Artificial intelligence is now everywhere in drug discovery. Graph neural network, Transformers and diffusion models scan large libraries, rank hits, and even invent new molecules. This speed and scale are impressive, but there is a quiet problem underneath: many of these systems treat molecules as if they were flat. They see graphs, strings and numbers, not handed three dimensional objects. In other words, they are often blind to chirality.

This first episode introduces the idea of chiral bias in AI driven drug discovery. We look at what chirality is, why it matters so much in pharmacology, and how our current data and representations allow AI to learn chemistry without really learning stereochemistry. The later episodes pick up from here and follow the consequences through screening, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET), and generative design, then into possible fixes and broader cultural questions.

1.1 The AI boom in molecular discovery

If you look at modern early discovery work, one pattern stands out. Before anyone orders a compound or sets up a reaction, someone says, “Let us see what the model thinks.” A few examples.

- Deep learning QSAR models predict potency, selectivity and off target risks directly from structure.

- Machine learning scoring functions triage docking results and virtual screens.

- Generative models based on VAEs, GANs, reinforcement learning or diffusion suggest new structures that trade off potency, solubility and synthetic accessibility.

- Structural biology has been transformed by protein structure prediction. AlphaFold and related methods deliver reasonably accurate structures that feed straight into structure based design.

Libraries like DeepChem and a growing crop of commercial platforms have made these tools routine. A medicinal chemistry team can easily run a model over a million virtual molecules before a single analogue is synthesized. This is not hype. Done properly, these methods really do:

- Cut down the number of dead synthesis ideas.

- Highlight structure activity patterns that are not obvious by eye.

- Focus expensive assays on the most promising slice of chemical space.

The question is not whether AI is useful, but what exactly it is learning.

1.2 Chirality in plain language

Chirality is the old story of left and right hands, but applied to molecules. A molecule is chiral if its mirror image cannot be superimposed on it. The two mirror forms are enantiomers. They have the same atoms and the same connectivity, but in three dimensions they are arranged differently in space.

In most achiral environments, the two enantiomers share many physical properties. They have the same boiling point, melting point and basic logP. Biology is not achiral. Proteins are built from L amino acids. DNA is right handed. Enzymes, receptors and transporters are all chiral objects.

That means that the two enantiomers can behave very differently once inside a body. Textbook examples still matter.

- Thalidomide is the standard horror story. One enantiomer had the desired sedative and antiemetic effect. The other was teratogenic and caused severe birth defects. The drug racemizes in vivo, so the story is more complex than “one good, one evil”, but it shows how sensitive biology is to handedness.

- Propranolol, the S enantiomer is the potent beta blocker. The R form is around two orders of magnitude less active at the receptor.

- Methadone provides another lesson. The R enantiomer drives the desired analgesic effect. The S enantiomer is closely associated with hERG binding and QT prolongation risk.

Medicinal chemists are used to thinking in terms of eutomer, distomer and chiral switch. They know that the three dimensional arrangement of atoms can be the difference between a blockbuster and a disaster. So far, this is standard stereochemistry. The trouble starts when this three dimensional reality is turned into the inputs that AI systems actually consume.

1.3 How AI “sees” molecules

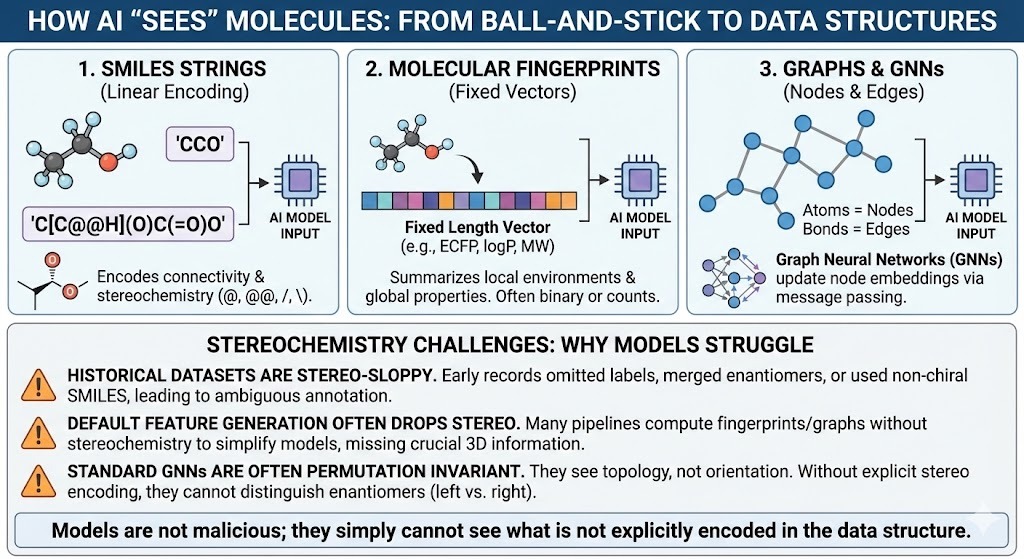

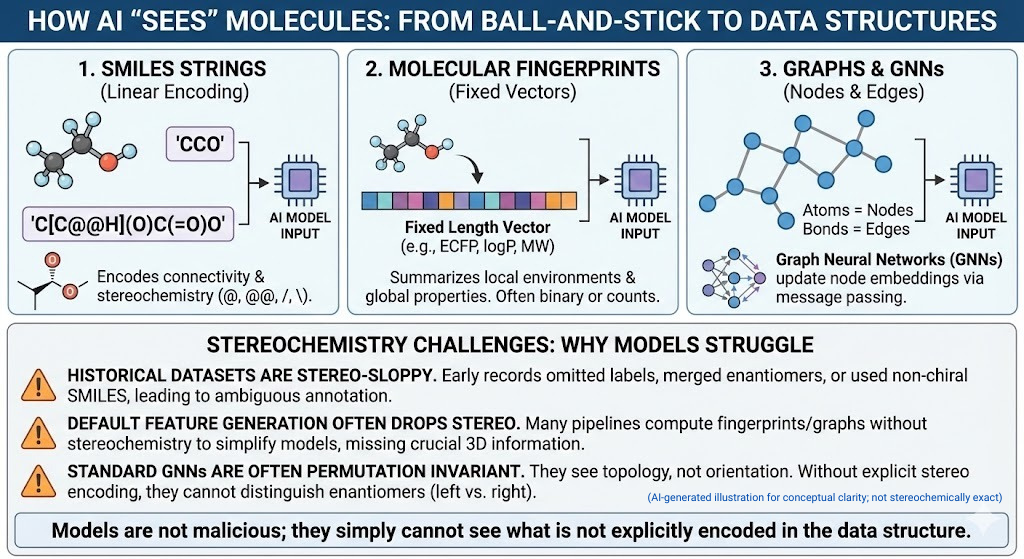

Models do not see cute ball and stick drawings. They see data structures. Three families dominate.

- SMILES strings. Linear encodings of connectivity such as CCO for ethanol. SMILES can encode chirality with characters like @ and @@ and slash or backslash for E or Z double bonds.

- Molecular fingerprints and descriptors. Fixed length vectors that summarize local environments and global properties. Extended connectivity fingerprints such as ECFP, along with logP, molecular weight and so on.

- Graph neural networks pass messages along edges and update node embeddings. Graphs. Atoms become nodes. Bonds become edges.

All of these can in principle represent stereochemistry. In practice three things keep going wrong.

- Historical datasets are stereo-sloppy. Early registration systems routinely omitted stereochemical labels, used non-chiral SMILES strings to encode racemates, or collapsed enantiomers into a single record. Decades later, these practices still echo through public and corporate databases, leaving behind ambiguous, incomplete, or outright incorrect stereochemical annotations—a hidden problem that modern AI models unknowingly inherit.

- Default feature generation often drops stereo. Many pipelines compute fingerprints with stereochemistry turned off because the gains on standard benchmarks do not justify the extra complexity. Graph features are often purely 2D.

- Most graph neural networks are designed to be invariant under permutation and graph isomorphism. Two enantiomers are graph isomorphic. If your model only sees topology, not orientation, it has no way to distinguish left from right.

Recent studies have made this painfully clear. Gaiński and colleagues, Liu and co-workers, and more recently Yan et al. all asked, in different ways, a version of the blunt question: are deep learning models actually aware of chirality?

Across these investigations, the researchers constructed benchmark tasks in which enantiomers were assigned different biological or physicochemical labels. The results were strikingly consistent: standard 2D GNNs and many classical descriptor-based models failed outright, because they effectively collapsed enantiomers into the same representation. Only when stereochemistry was explicitly encoded and used—whether through chiral message-passing layers, 3D-aware architectures, or dedicated stereochemical feature extraction—did model performance recover.

The models were not malicious; they simply could not see the stereochemical information that was never provided to them.

1.4 Chiral bias as an information problem

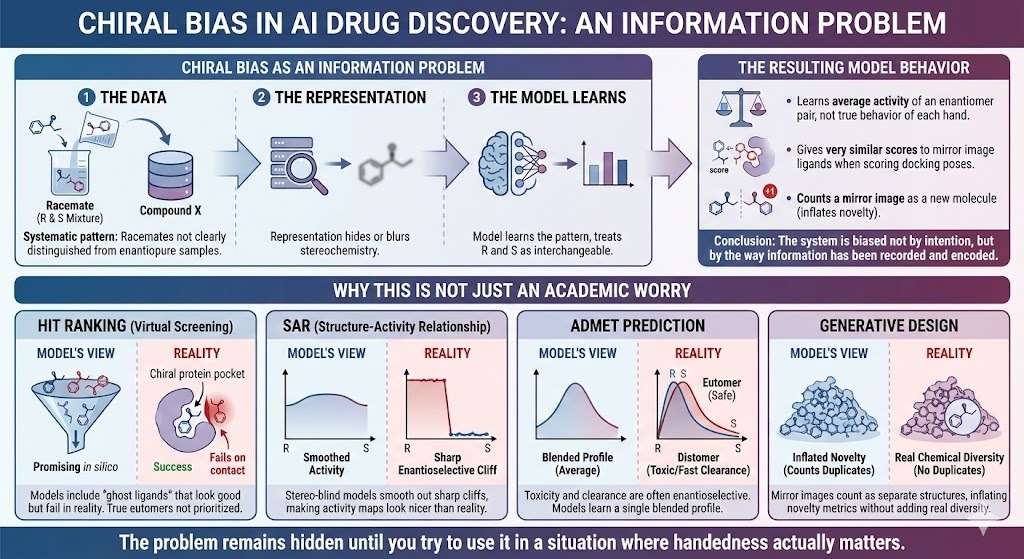

We usually talk about bias in AI in social contexts. There the concern is biased training data and unfair decisions. Chiral bias looks different on the surface, but structurally it is similar.

- There is a systematic pattern in the data. Racemates are not clearly distinguished from enantiopure samples.

- The representation often hides or blurs stereochemistry.

- The model learns the patterns that are present, and so treats R and S (stereo-descriptors) as interchangeable.

The result is a model that:

- Learns the average activity of an enantiomer pair instead of the true behaviour of each hand.

- Gives very similar scores to mirror image ligands when scoring docking poses.

- Counts a mirror image of a known drug as a new molecule instead of what it is, namely an inverted copy.

This is what we mean by chiral bias in AI drug discovery. The system is biased not by intention, but by the way information has been recorded and encoded.

1.5 Why this is not just an academic worry

It might be tempting to say, “We have been using these models for years and they seem fine.” Look at where the bias bites.

- In hit ranking, virtual screening models that ignore stereo will include ghost ligands. These are mirror images that look promising in silico and fail on contact with a chiral pocket. At the same time, the true eutomer is not given extra weight.

- In SAR, models trained on racemic data with stereo blind representations smooth out sharp enantioselective cliffs. Structure activity maps look nicer than reality because the cliff between left and right has been averaged away.

- In ADMET prediction, toxicity and clearance can be strongly enantioselective. Models that ignore this learn a single blended profile that does not correspond to any real formulation.

- In generative design, mirror images count as separate structures. Novelty metrics are inflated by mirror duplicates that add no real chemical diversity.

A model validated on benchmarks that share the same stereochemical flaws will still post impressive metrics. The problem remains hidden until you try to use it in a situation where handedness actually matters.

1.6 Where the series goes from here

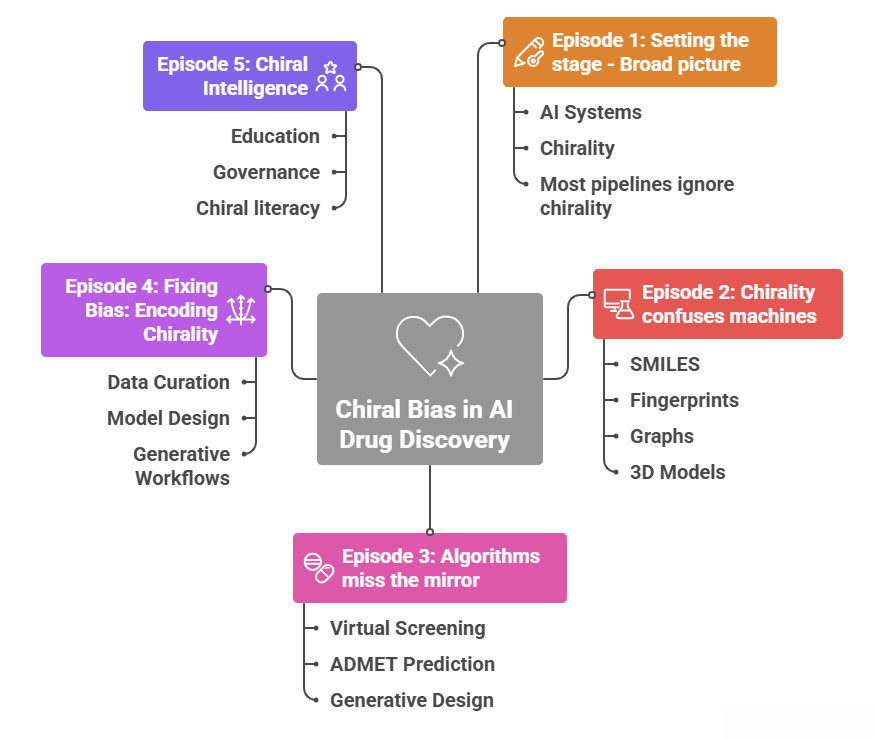

This first part set up the broad picture.

- AI systems are genuinely changing how early discovery is done.

- Chirality is central to pharmacology and cannot be hand waved away.

- Many of the systems we use have been trained and validated in an effectively achiral universe.

The rest of the series drills down.

- Episode 2 goes into more detail on SMILES, fingerprints, graphs and 3D models and shows exactly how they lose or flatten stereochemistry, and how common architectures inherit that blind spot.

- Episode 3 follows the consequences through virtual screening, ADMET prediction and generative design, connecting them to familiar pharmacology examples.

- Episode 4 looks at data curation and model design that explicitly encode chirality, and at generative workflows that respect stereochemistry instead of abusing it.

- Episode 5 steps back and talks about chiral literacy, education and governance, using the warnings from Moores and Zuin Zeidler as a guide.

References

Moores A, Zuin Zeidler VG. Don’t let generative AI shape how we see chemistry. Nat Rev Chem. 2025 Oct;9(10):649-650. doi: 10.1038/s41570-025-00757-9.

Brian Buntz, How stereo-correct data can de-risk AI-driven drug discovery. https://www.drugdiscoverytrends.com/how-stereo-correct-data-can-de-risk-ai-driven-drug-discovery/. News Release: 15 October, 2025

Yasuhiro Yoshikai, Tadahaya Mizuno, Shumpei Nemoto & Hiroyuki Kusuhara. Difficulty in chirality recognition for Transformer architectures learning chemical structures from string representations. Nat Commun 15, 1197, 2024. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-45102-8

Daniel S. Wigh, Jonathan M. Goodman, Alexei A. Lapkin. A review of molecular representation in the age of machine learning. The WIREs Computational Molecular Science, 12, 5, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1603

Derek van Tilborg, Alisa Alenicheva, Francesca Grisoni. Exposing the Limitations of Molecular Machine Learning with Activity Cliffs. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 23, 5938-5951. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.2c01073

Dagmar Stumpfe, Huabin Hu, Jürgen, Bajorath. Evolving Concept of Activity Cliffs. ACS Omega, 4, 11, 14360-14368, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b02221

Ramsundar, B.; Eastman, P.; Walters, P.; Pande, V. Deep Learning for the Life Sciences: Applying Deep Learning to Genomics, Microscopy, Drug Discovery, and More. O’Reilly Media, 2019. ISBN 9781492039839.

Walters WP, Barzilay R. Applications of Deep Learning in Molecule Generation and Molecular Property Prediction. Acc Chem Res. 2021 Jan 19;54(2):263-270. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00699.

Sanchez-Lengeling B, Aspuru-Guzik A. Inverse molecular design using machine learning: Generative models for matter engineering. Science. 2018 Jul 27;361(6400):360-365. doi: 10.1126/science.aat2663.

Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2

Gaiński, P.; Koziarski, M.; Tabor, J.; Śmieja, M. ChiENN: Embracing Molecular Chirality with Graph Neural Networks. In: Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer, 2023; DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-43418-1_3.

Liu, Y.; et al. Interpretable Chirality-Aware Graph Neural Network for Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship Modeling. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2023.

Yan, J.; et al. Interpretable Algorithm Framework of Molecular Chiral Graph Neural Network for QSAR Modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.4c02259.

Ariens EJ. Stereochemistry, a basis for sophisticated nonsense in pharmacokinetics and clinical pharmacology. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 1984 26, 663 to 668.

Kruithof, P.; et al. “Practical aspects of stereochemistry in cheminformatics and molecular modeling.”

Journal of Cheminformatics 2021, 13, 1–26. doi: 10.1186/s13321-021-00519-8

Fourches, D.; Muratov, E.; Tropsha, A. “Trust but verify: on the importance of chemical structure curation in cheminformatics.” J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 1189–1204. doi: 10.1021/ci100176x

Zdrazil B, Felix E, Hunter F, Manners EJ, Blackshaw J, Corbett S, de Veij M, Ioannidis H, Lopez DM, Mosquera JF, Magarinos MP, Bosc N, Arcila R, Kizilören T, Gaulton A, Bento AP, Adasme MF, Monecke P, Landrum GA, Leach AR. The ChEMBL Database in 2023: a drug discovery platform spanning multiple bioactivity data types and time periods. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024 Jan 5;52(D1):D1180-D1192. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad1004.

Schuett KT, Kindermans PJ, Sauceda HE, et al. SchNet: a continuous filter convolutional neural network for modeling quantum interactions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (2017), pp. 992-1002. doi/10.48550/arXiv.1706.08566

Testa B, Trager WF. Drug Metabolism: Chemical and Enzymatic Aspects. CRC Press, 1995.

Tom G, Yu E, Yoshikawa N, Jorner K, Aspuru-Guzik A. Stereochemistry-aware string-based molecular generation. PNAS Nexus. 2025 Oct 14;4(11):pgaf329. doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf329.

Yaëlle Fischer, Thibaud Southiratn, Dhoha Triki, Ruel Cedeno. Deep Learning vs Classical Methods in Potency & ADME Prediction: Insights from a Computational Blind Challenge. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5c01982.

Schneider N, Lewis RA, Fechner N, Ertl P. Chiral Cliffs: Investigating the Influence of Chirality on Binding Affinity. ChemMedChem. 2018 Jul 6;13(13):1315-1324. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201700798.

Husby J, Bottegoni G, Kufareva I, Abagyan R, Cavalli A. Structure-based predictions of activity cliffs. J Chem Inf Model. 2015 May 26;55(5):1062-76. doi: 10.1021/ci500742b.

Further Reading

Eliel, E. L., & Wilen, S. H. Stereochemistry of organic compounds. John Wiley & Sons. 1994.

Eliel & Wilen repeatedly caution that “sloppy usage of stereochemical terms” leads to incorrect interpretation of structure, properties, and reactivity. They emphasize that stereochemical descriptors must be used precisely and consistently, and warn instructors to avoid careless or ambiguous usage.

Presumably the situation will improve & this inconsistency will inevitably be overcome with further development & associated refinement.

I share your optimism — refinement will come.

But improvement isn’t automatic. If the data and benchmarks remain stereo-sloppy, models may simply become more confidently wrong in 3D.

The real shift happens when we intentionally teach AI to see the mirror — not just scale the machine.