“Science, ethics, and clinical outcomes converge at a difficult question -does the purer mirror image truly heal better?”

Introduction

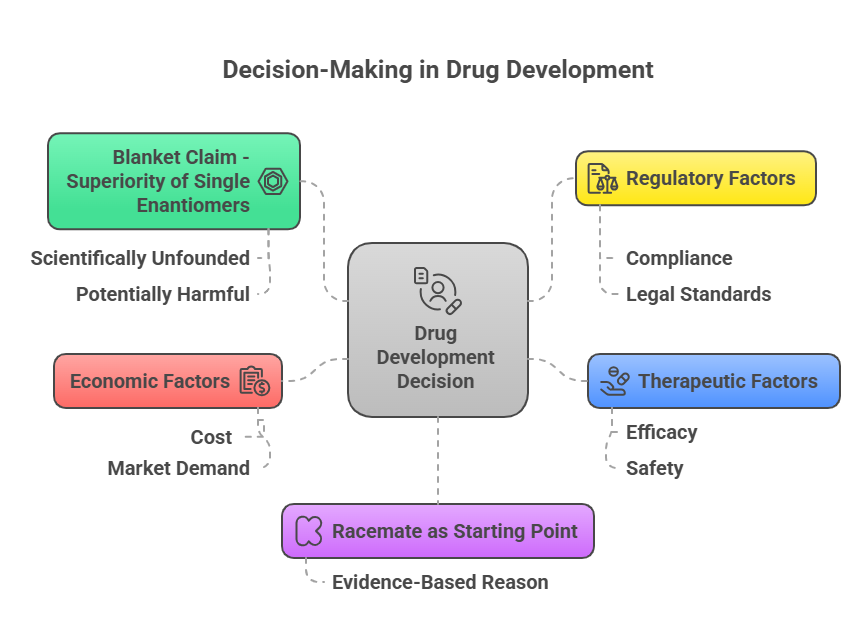

The development of single-enantiomer drugs has been heralded as a leap forward in pharmacotherapy, promising greater efficacy, reduced side effects, and more predictable pharmacokinetics. But as the pharmaceutical industry increasingly embraced chiral switches and single-enantiomer innovations, an important clinical question arose: Are single enantiomers always better than their racemic predecessors? In this episode, we critically examine the clinical evidence, ethical debates, regulatory perspectives, and payer considerations surrounding single-enantiomer drugs. We explore whether single enantiomers truly offer meaningful advantages -or if the reality is more nuanced.

The Theoretical Advantages of Single Enantiomers

From a scientific standpoint, several theoretical benefits favor single-enantiomer development:

- Target specificity: A pure eutomer may interact more selectively with the desired biological target, minimizing off-target effects (Jamali & Mehvar, 1994).

- Reduced dose: If the distomer is inactive or counterproductive, eliminating it can lower the therapeutic dose.

- Simplified pharmacokinetics: Single-enantiomer drugs can exhibit less interindividual variability.

- Predictable metabolism: Avoiding stereoselective metabolism may simplify drug interactions and clearance.

Regulatory guidance, such as the FDA’s 1992 Policy Statement, reflects these theoretical advantages but does not assume superiority without proof (FDA, 1992).

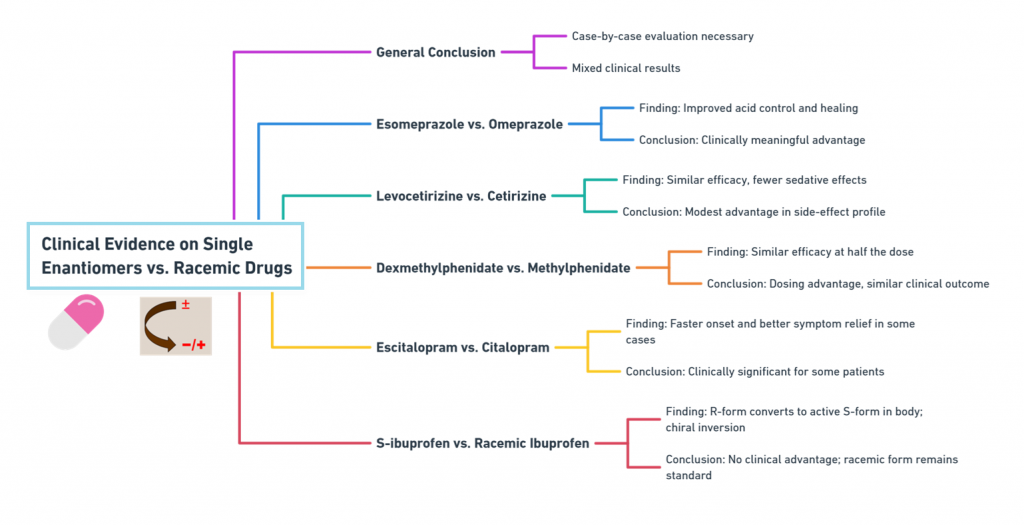

What the Clinical Evidence Shows: Case-by-Case Evaluation

Despite the appealing theory, clinical superiority of single enantiomers must be demonstrated empirically -and the results have been mixed.

1. Esomeprazole vs. Omeprazole

- Findings: Esomeprazole (S-enantiomer) showed improved acid control and healing rates compared to omeprazole, particularly at standard doses (Andersson, 2001).

- Conclusion: Clinically meaningful advantage achieved.

2. Levocetirizine vs. Cetirizine

- Findings: Levocetirizine demonstrated similar efficacy with slightly fewer sedative effects compared to cetirizine (Simons, 2004).

- Conclusion: Modest advantage, particularly in side-effect profile.

3. Dexmethylphenidate vs. Methylphenidate

- Findings: Dexmethylphenidate enabled similar efficacy at half the dose (Quinn et al., 2007).

- Conclusion: Dosing advantage, but clinical outcome similar.

4. Escitalopram vs. Citalopram

- Findings: Some studies suggest escitalopram (S-enantiomer) offers faster onset and greater symptom relief for depression (Burke et al., 2002).

- Conclusion: Clinically significant in some patient populations.

5. S-ibuprofen vs. racemic ibuprofen

- Findings: Despite the S-enantiomer being active, racemic ibuprofen remains the clinical standard because the R-form undergoes metabolic chiral inversion in vivo (Lee & Jamali, 2006).

- Conclusion: No significant clinical difference justifying switch.

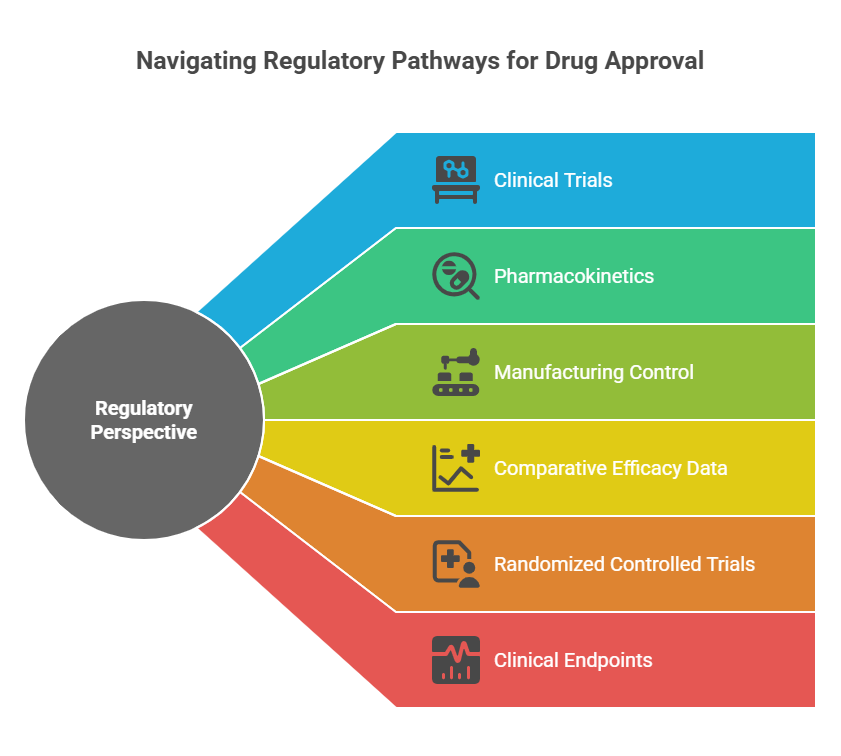

Regulatory Perspective: Clinical Benefit is Not Assumed

FDA, EMA, and other agencies emphasize:

- Superiority must be demonstrated through clinical trials, not assumed based on purity.

- Improvements in pharmacokinetics or manufacturing control alone are insufficient without corresponding clinical outcomes.

- New marketing authorization for a single enantiomer often requires comparative efficacy data.

Regulatory submissions for chiral switches must thus include:

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) vs. the racemate.

- Clinical endpoints showing statistically and clinically meaningful improvements.

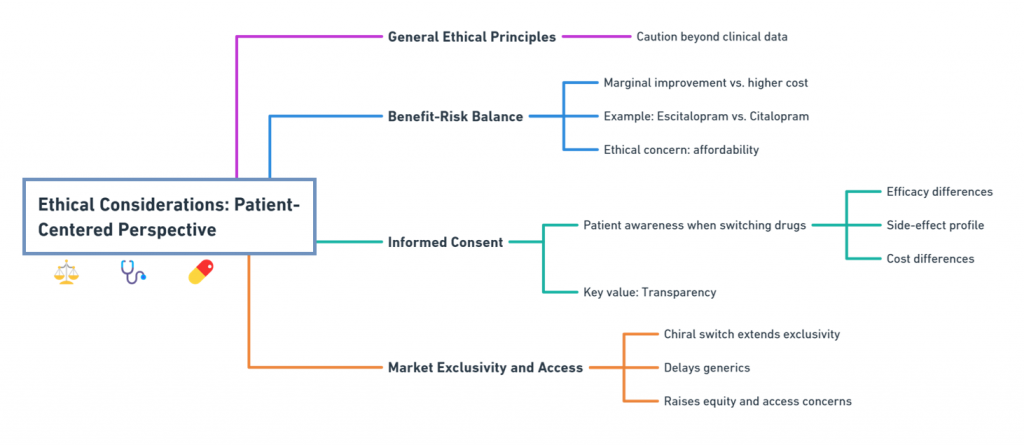

Ethical Considerations: Patient-Centered Perspective

Beyond clinical data, ethical principles call for caution:

1. Benefit-Risk Balance

If the single enantiomer offers only marginal improvements but commands a much higher price, is it ethical to promote it over the generic racemate?

- For instance, escitalopram offers modest benefits over citalopram, but at a significantly higher cost -raising affordability concerns (Burke et al., 2002).

2. Informed Consent

Patients must be informed when switching from a racemate to a single-enantiomer drug:

- Differences in efficacy.

- Differences in side-effect profiles.

- Differences in cost.

Transparency is key to maintaining trust.

3. Market Exclusivity and Access

Chiral switches can delay generic competition if framed as new drugs, leading to prolonged periods of higher prices -a concern for health equity advocates (Agranat & Wainschtein, 2010).

Payer and Health System Perspectives

Payers -including insurance companies and public health systems -increasingly scrutinize the cost-benefit of single-enantiomer drugs:

- Value-based coverage: Coverage decisions are now often based on comparative effectiveness studies.

- Step therapy: Some payers require patients to try (and fail) generic racemates before approving single-enantiomer versions.

- Formulary decisions: Drugs offering only marginal benefits may be placed on higher co-pay tiers.

Thus, even if regulators approve a single enantiomer, real-world utilization depends on demonstrated value.

Factors That Favor Clinical Adoption of Single Enantiomers

Single enantiomers tend to be favored clinically when they:

- Offer clearly superior therapeutic outcomes.

- Significantly reduce side effects or improve safety.

- Simplify dosing regimens.

- Show reduced variability across patient populations.

- Address unmet medical needs not fully satisfied by the racemate.

Without these advantages, clinicians often prefer lower-cost racemates, especially if outcomes are comparable.

Examples Where Single Enantiomers Did Not Dominate

Not all single-enantiomer launches have succeeded:

- Arformoterol (R-enantiomer of formoterol): Despite some PK advantages, it did not dramatically outperform formoterol in COPD treatment.

- Dextromethorphan (DM) versus racemic mixtures: DM remains the standard for cough suppression, despite theoretical advantages.

These cases highlight that scientific plausibility does not guarantee clinical success.

Emerging Trends: Personalized Medicine and Chirality

As personalized medicine advances:

- Pharmacogenomics will help identify subpopulations that might benefit more from single-enantiomer formulations.

- Enantiospecific therapies might be developed directly based on genetic profiles, reducing the need for post-market chiral switches (Zhou, 2011).

Thus, the future of single enantiomers may be more precision-driven, rather than one-size-fits-all.

Conclusion

Single-enantiomer drugs represent an important advance in pharmaceutical science -but their clinical superiority over racemates cannot be assumed. Each case must be evaluated based on hard clinical data, careful ethical analysis, and clear benefit-risk assessment. Regulators, payers, prescribers, and patients all have critical roles in ensuring that when one mirror image replaces two, it truly reflects better healing.

In the next episode, we will turn our attention to the ethical and economic dimensions of chiral drugs -exploring how regulatory decisions intersect with intellectual property, access, and trust.

What is in the next episode?

“Beyond molecules and mirrors lies money and meaning. Join us for Episode 8: Beyond the Approval: Ethical and Economic Dimensions of Chiral Drugs.“

References

Israel Agranat & Ilaria D’Acquarica (2025), Racemic drugs are not necessarily less efficacious and less safe than their single-enantiomer components. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2025.107082

Agranat, I., & Wainschtein, S. R. (2010). The strategy of enantiomer patents of drugs. Drug Discovery Today, 15(5-6), 163–170.

Andersson, T. (2001). Pharmacokinetics, metabolism and interactions of acid pump inhibitors: Focus on omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 40(7), 523–538.

Burke, W. J., Gergel, I., & Bose, A. (2002). Fixed-dose trial of the single isomer SSRI escitalopram in depressed outpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 63(4), 331–336.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (1992). Development of New Stereoisomeric Drugs (Policy Statement). Federal Register, 57(88), 22249–22250.

Jamali, F., & Mehvar, R. (1994). Role of stereoselectivity in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Biochemical Pharmacology, 48(4), 605–616.

Lee, E. J., & Jamali, F. (2006). Clinical pharmacokinetics of ibuprofen. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 6(5), 402–415.

Quinn, D., Bode, R., Bialer, P., & The Focalin Study Group. (2007). Dexmethylphenidate hydrochloride versus methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(5), 719–725.

Simons, F. E. (2004). Advances in H1-antihistamines. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(21), 2203–2217.

Zhou, S. F. (2011). Drugs behave as substrates, inhibitors and inducers of human cytochrome P450 3A4. Current Drug Metabolism, 9(4), 310–322.