The Mirror We Build Defines the World We Keep; Decoding the Science, the Risks, and the Responsibility

Synopsis: Mirror Life: When Chemistry Meets Philosophy

Recently, Scientific American published two striking pieces that push chemistry into almost philosophical territory:

- Vaughn S. Cooper, “Deadly ‘Reverse’ Cells Can Destroy Us Unless Scientists Stop Them” (Jan 20, 2026)

- Simon Makin, “Creating ‘Mirror Life’ Could Be Disastrous, Scientists Warn” (Dec 14, 2024)

Both ask a radical question: what if we rebuilt life itself using mirror‑image molecules?

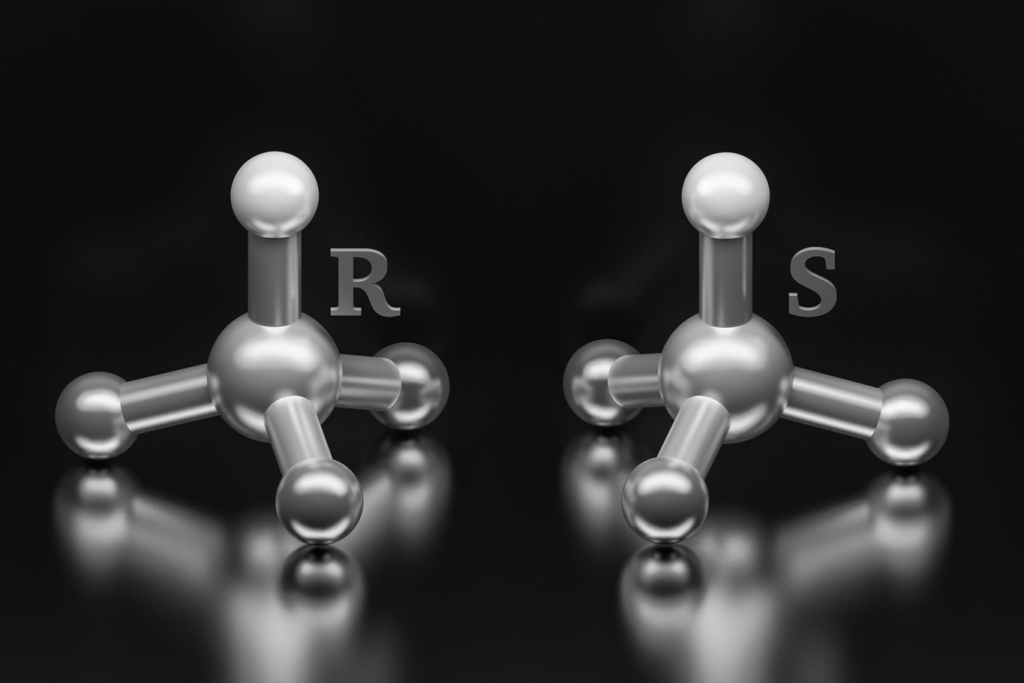

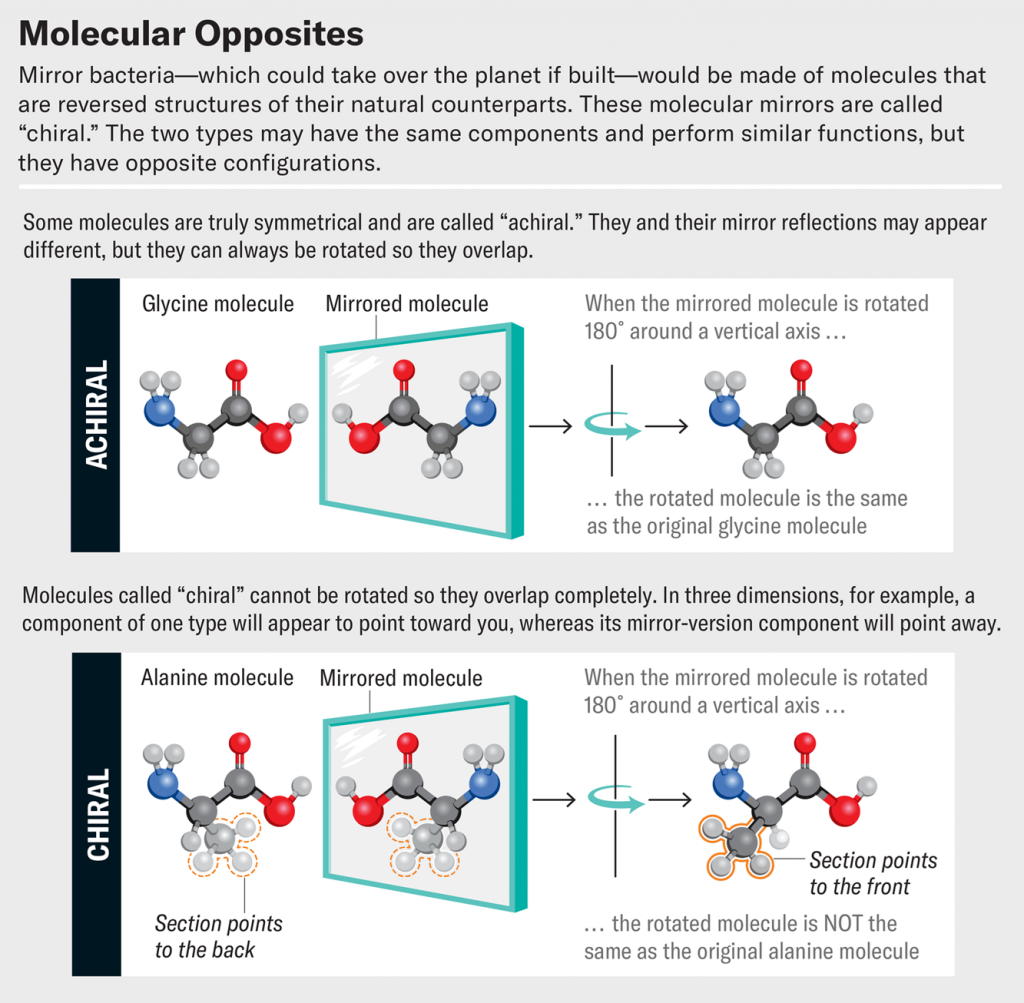

For decades, chirality—the “handedness” of molecules—has been the quiet backbone of medicinal chemistry. We’ve argued over single enantiomers versus racemates, perfected stereoselective synthesis, and built regulatory frameworks to keep drugs safe. In that world, chirality is a design choice: tweak it for better absorption, cleaner targeting, fewer side effects.

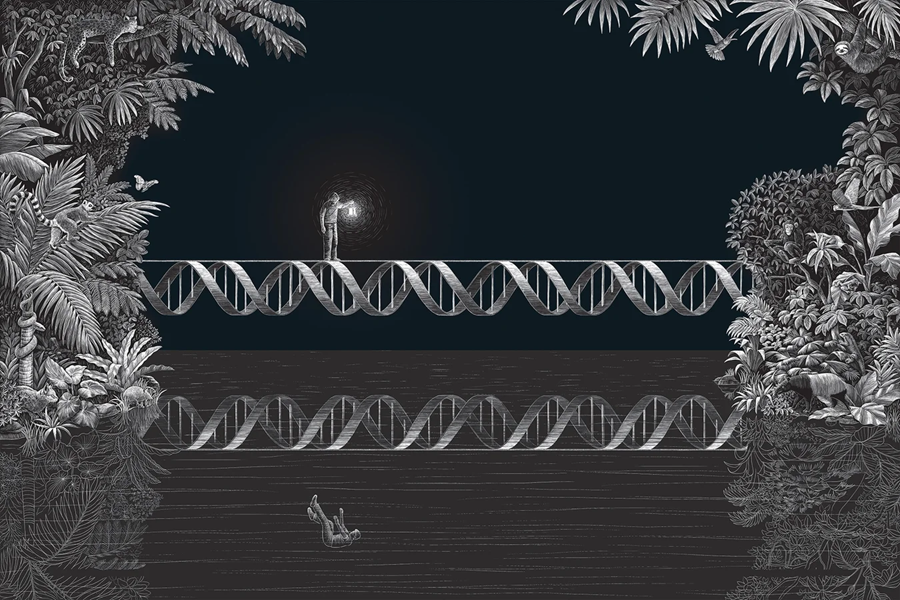

But mirror life takes chirality out of the lab notebook and into the biosphere. It’s not about optimizing a drug anymore—it’s about flipping the molecular architecture that underpins all biology. Imagine proteins, DNA, and enzymes built as mirror images of the ones we know. Would they thrive alongside us, or threaten the systems our immune defenses evolved to protect?

The Scientific American articles treat this not as science fiction, but as a real horizon. They map out the progress already made, the tantalizing benefits, and the ecological and medical risks. Most importantly, they raise a governance alarm: science may be racing ahead faster than our ability to set boundaries.

And here’s why this matters for all of us: in a world of short attention spans and dense technical papers, even seasoned chemists and biologists may not have time to unpack every nuance. This blog aims to translate those complex discussions into a clear, structured story—one that preserves the science but makes the implications accessible. Because when chirality shifts from drug design to biosphere design, the conversation isn’t just technical anymore. It’s existential.

Chirality: Life’s Hidden Rulebook

Think about your hands. They look the same, but try to place one on top of the other—they don’t quite match. That simple idea of “handedness” is chirality, and it runs deep into the molecular fabric of life.

They are chemically identical in composition but distinct in three-dimensional orientation.

Biology recognizes that difference immediately.

The question is — do our digital models? 🧬📐🤖

At the chemical level, two molecules can be identical in composition yet differ in their three‑dimensional orientation. Biology notices that difference instantly. The question is—do our digital models notice it too? 🧬📐🤖

Life on Earth plays by a striking rule: molecules are overwhelmingly one‑handed. Proteins are stitched together from left‑handed amino acids. DNA and RNA spiral with right‑handed sugars. This isn’t a decorative quirk—it’s the foundation of how biology works. Enzymes fit their substrates like keys in locks. Receptors recognize signals through precise stereochemical matches. Antibodies detect pathogens by shape.

In short, life is a dance of chiral fits. Flip a molecule into its mirror image, and suddenly the choreography breaks. What looks chemically similar may fail to bind, signal, or protect. That’s why chirality isn’t optional—it’s indispensable.

Yet synthetic biology is steadily rewriting the rules. The same tools that let us edit genomes and build complex biomolecules now open the door to something startling: mirror versions of life’s molecules, constructed deliberately. What once sounded like a thought experiment is edging closer to a technical frontier. And if that frontier extends to whole organisms, the implications stretch far beyond medicine—to the very stability of Earth’s biosphere.

What Is “Mirror Life”?

Imagine organisms built from molecules that are flipped like reflections in a mirror. Instead of the left‑handed amino acids that make up our proteins, they would use right‑handed ones. Instead of right‑handed DNA, their genetic material would twist in the opposite direction. Every part of the cell—enzymes, ribosomes, membranes—would be reversed.

This isn’t just speculation. Scientists have already created mirror versions of individual biomolecules, including DNA fragments and proteins. As Scientific American reported in December 2024, building a complete mirror bacterium would still require major breakthroughs—but the roadmap exists. The question is no longer can we make mirror molecules, but should we ever assemble them into living organisms?

Why Build Mirror Biology at All?

The idea didn’t come from recklessness. It grew out of practical hopes:

- Drug stability: Many medicines are quickly broken down by enzymes. Mirror‑image drugs might resist this breakdown, lasting longer in the body.

- Immune evasion (for good): Mirror peptides could slip past immune recognition, reducing unwanted side effects.

- Industrial resilience: Biotech factories often rely on bacteria to produce pharmaceuticals, but these bacteria are vulnerable to viral infections. Mirror bacteria might be immune to natural viruses, making production more secure.

These possibilities explain why mirror biology was first greeted with optimism.

The Central Concern: Immune Evasion

The alarm bells ring when mirror life moves beyond controlled labs. What if a mirror bacterium escaped into the world?

Our immune system is tuned to recognize the molecular “handedness” of pathogens. Macrophages and neutrophils engulf bacteria using enzymes shaped for natural biomolecules. Flip those molecules, and recognition may fail. As Scientific American warned in January 2026, mirror pathogens could evade both innate and adaptive immunity.

Adaptive defenses might falter too. T cells rely on antigen presentation—breaking microbial proteins into fragments the immune system can recognize. Mirror proteins might not be processed at all, leaving the body blind to the invader.

The danger isn’t that mirror pathogens would be unstoppable, but that they could slip past multiple layers of defense at once. That possibility is enough to turn mirror life from a scientific curiosity into a global biosecurity debate.

Ecological Implications: Beyond Human Health

The risks of mirror life don’t stop at infections in humans. Ecosystems themselves could be shaken. Microbial communities are held in balance by predators, competitors, and viruses. Bacteriophages, for example, infect bacteria by recognizing surface molecules with exquisite precision. Amoebae and other microbial hunters consume bacteria through molecular cues honed by evolution.

Now imagine mirror bacteria—cells built from reversed molecules. Those predators and viruses might simply fail to recognize them. As Scientific American warned in January 2026, such organisms could spread unchecked, slipping past the natural controls that keep ecosystems stable.

Take photosynthetic microbes like cyanobacteria. If mirror versions could capture sunlight and carbon dioxide while resisting viral attack, they might multiply without limit. Marine food webs depend on microbial balance. A disruption at the base could ripple upward, affecting fisheries and even larger ocean species. These scenarios remain hypothetical, but they highlight how mirror life could reshape not just medicine, but the planet’s ecology.

How Close Are We?

It’s important to stay grounded. No complete mirror bacterium exists today. Building one would mean synthesizing long mirror DNA strands, assembling mirror ribosomes, and constructing a fully functional cell from reversed components. As noted in January 2026, this would demand resources on the scale of a scientific megaproject.

In other words, mirror life is not imminent. The debate is anticipatory—scientists are trying to weigh risks before the technology matures.

The Debate Within Science

Here, opinions diverge. Some researchers argue mirror bacteria might struggle to survive outside controlled labs, facing competitive disadvantages. Others warn against premature restrictions, likening them to banning transistors out of fear of cybercrime—a comparison made by Andrew Ellington in December 2024.

But the authors of the warning articles take a precautionary stance. They argue that given the possibility of irreversible ecological or health consequences, international dialogue and governance frameworks are essential. Some even suggest a moratorium on constructing full mirror organisms until safety assessments are more complete.

The goal isn’t to halt science—it’s to ensure its trajectory aligns with global safety.

Chirality as a Biospheric Principle

What makes the mirror‑life debate so profound is that it reframes chirality not just as a chemical curiosity, but as a planetary rulebook. Life’s uniform handedness is what allows immune systems to recognize invaders, ecosystems to stay balanced, and evolution to build on itself without collapsing. Introduce a parallel biochemistry with the opposite orientation, and suddenly you have a system that doesn’t play by those rules.

For centuries, scientists puzzled over why life chose one orientation over the other. Now, for the first time, we face the possibility of deliberately constructing the alternative. That marks a shift—from explaining asymmetry to engineering it.

Conclusion: Looking into the Molecular Mirror

The conversation around mirror life isn’t fueled by hype. It’s fueled by foresight. As Scientific American noted in January 2026, history is full of technologies whose risks were recognized only after harm had already occurred. Mirror life is unusual in that scientists are debating the dangers before irreversible consequences unfold.

Whether mirror organisms ever come to life will hinge not just on scientific breakthroughs, but on collective wisdom. The research is moving forward, but the rules to guide it are still being written. What’s striking is how chirality—once tucked away in stereochemistry diagrams—has stepped into the spotlight as part of a global conversation about responsibility.

Mirror life challenges us to pause at the edge of possibility. When science gives us the power to flip the molecular foundations of biology, the question is no longer about capability—it’s about responsibility. How we choose to act will determine not just the trajectory of synthetic biology, but the resilience of the biosphere we all depend on.

Further reading